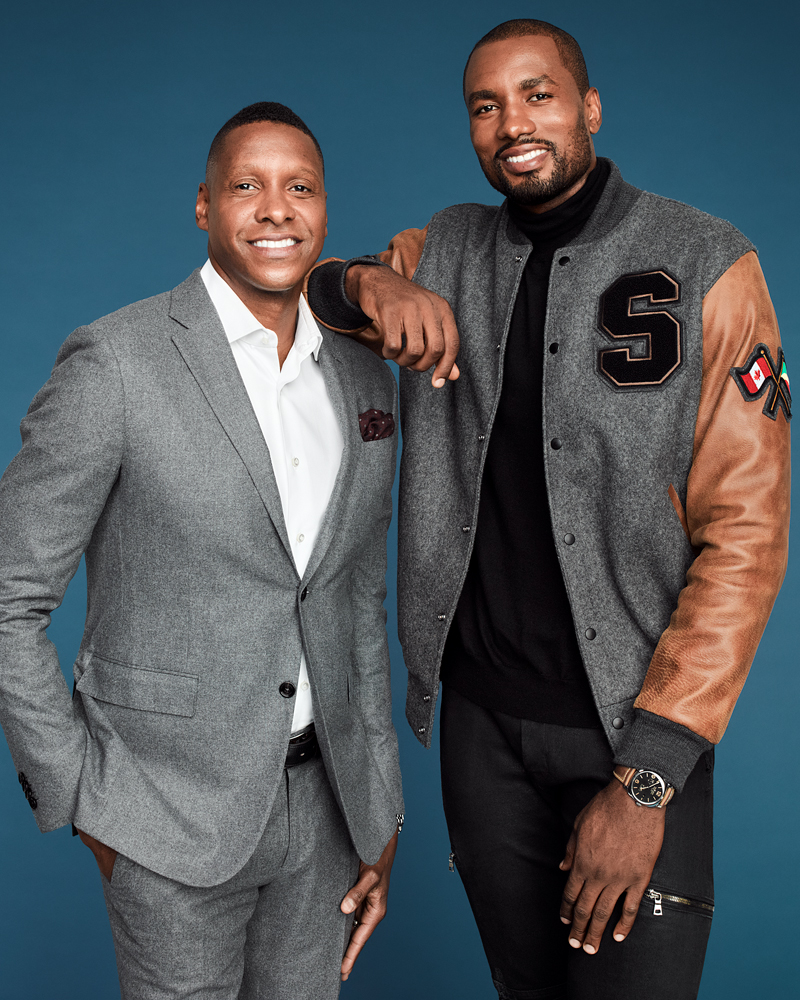

On Masai: Suit ($4,100) by Harry Rosen MTM. On Serge: Custom varsity jacket by Roots Canada; turtleneck ($425) by Z Zegna, available at Saks Fifth Avenue; watch ($15,900) by Panerai.

Masai Ujiri and Serge Ibaka greet each other warmly on set as we prepare for the day’s shoot. The two of them are kin not just by the team that they work for – Ujiri is the general manager of the Toronto Raptors, and Ibaka, a power forward – but from a shared foundation rooted deeply in their homeland.

On a bright Saturday afternoon, a few days before Thanksgiving, and amidst a chaotic scene filled with various members of the production crew and set, the two basketball giants have come together to talk about what they do off the court.

Ujiri and Ibaka are different than their contemporaries in a powerful way. To them, basketball is not only a passion that has driven them to summit an entire industry, but also something that has afforded them a unique opportunity to use their influence for good via their organizations, Giants of Africa and the Serge Ibaka Foundation.

To understand fully, one must go to their roots to appreciate the contributions they’ve made to their communities. Both have their origins in Africa, but the paths that they’ve followed to unite over a common cause have been radically divergent.

Puffer ($1,115) by Moncler; shirt ($500) by Harry Rosen MTM; jeans ($445) by Ermenegildo Zegna; watch and belt, Masai’s own.

ANOTHER WAY IN

“I remember that I was always happy. Sports made me happy.”

Ujiri grew up in Zaria, a major city in northern Nigeria, and was the son of a hospital administrator and doctor. His introduction to basketball happened when he was 13 through, of all things, soccer.

“My friends and I would always stop by this basketball court on the way to our games on the soccer field, where we’d start throwing the soccer balls into the baskets,” he recalls, a smirk emerging from the corner of his lips. “People started making fun of us for playing basketball with a soccer ball.”

It was on his way to the soccer field where he would meet Oliver B. Johnson, an American known only as coach OBJ, who would mentor young kids in the late afternoon before meeting with his players. This court, with soccer ball in hand, would be the origin for Ujiri’s basketball story.

The sport would soon consume him, keeping him awake at night as he dreamed of making it into the NBA. “All I had was a passion for basketball. I remember loving the game and being so intrigued with it.”

But his skills on the court wouldn’t be enough, and after six years of playing professionally in Europe, Ujiri would come to the realization that playing in the NBA wasn’t in his cards. Never one to accept defeat, he persisted and instead, diverted his efforts to find another way into the sport.

“I’ve always known how to get people’s attention. When I look back on my life and career, I know that’s helped me become a better leader. It’s about having command and making people believe in what you have to say,” says Ujiri.

That talent is one that aided him in his transition into management, helping him to connect with college coaches and NBA representatives, and eventually landing him his first big gig — as an unpaid scout for the Orlando Magic.

But Ujiri did whatever it took, bringing him to the brink of bankruptcy as he traveled around the world in search of new talent. It was that hustle and relentless pursuit of greatness that would eventually land him the role of international scout for the Denver Nuggets before ascending to his position as the first GM of African descent in NBA history.

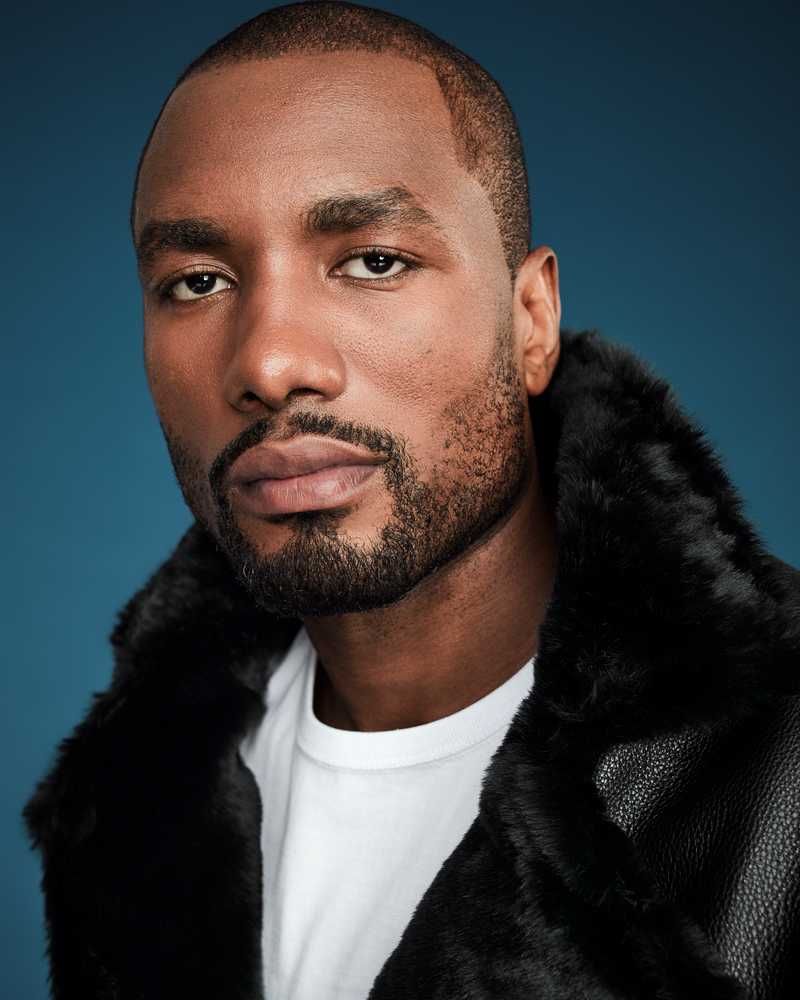

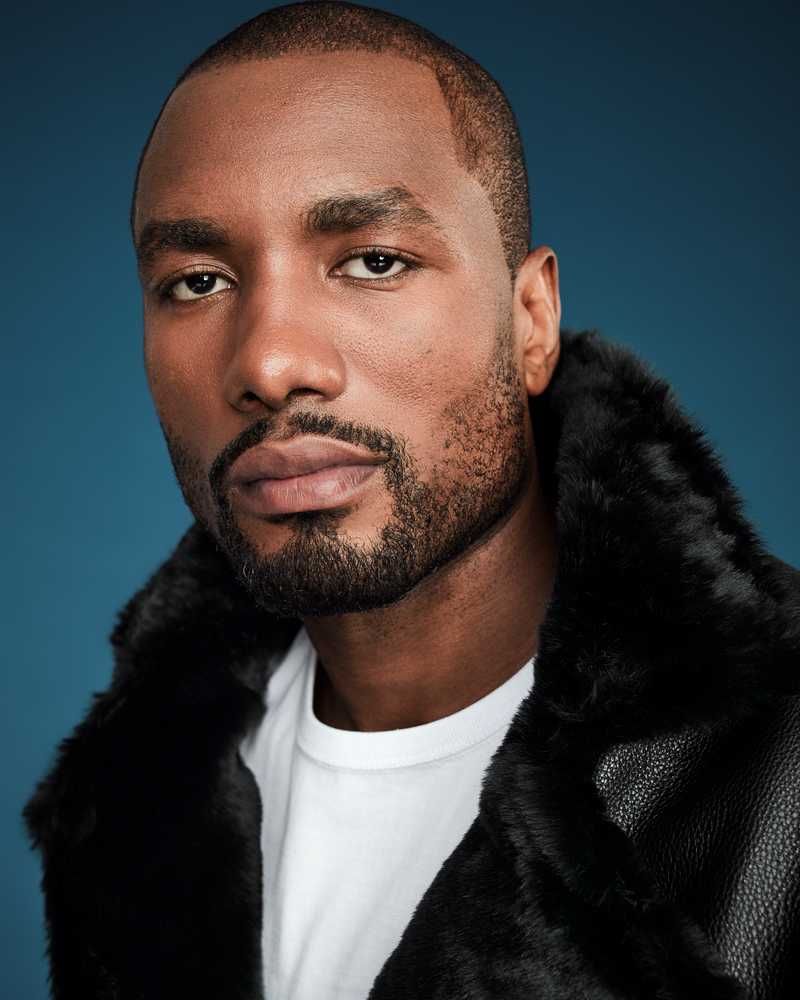

Jacket ($1,000) by Dangerfield, available at Park & Province; t-shirt ($35) by Kotn

WAR AND BASKETBALL

Ibaka was born on September 18, 1989, in the capital of the Republic of Congo, Brazzaville. Marked by the stark contrast between its rich culture and war, growing up in the impoverished nation placed many challenges in front of a young Ibaka. Being the son of two professional basketball players (his father played for the Republic of Congo national team, while his mother played for the Democratic Republic of Congo), the game was in Ibaka’s blood the moment he was born.

“THANK GOD I HAD BASKETBALL”

It was his love for the game that would carry Ibaka through some of the hardest moments of his life.

“Thank God I had basketball,” Ibaka reflects. “Sometimes I would wake up with an empty stomach and nothing to eat. But when you’re playing basketball, you forget about everything. I spent all day on those courts because I loved it so much.”

When he was eight, his mother passed away, and as he turned nine, Ibaka was forced to flee from Brazzaville as the Second Congo War caught fire and would go on to become the deadliest conflict after World War II, claiming more than five million lives. Upon returning to their home four years later, Ibaka’s father would then be captured and imprisoned for essentially being on the wrong side of the war.

Suit by Gotstyle Made-To-Measure; t-shirt ($35) by Kotn; sneakers ($655) by Lanvin, available at Saks Fifth Avenue; watch ($27,200) by Panerai.

Overcoming such hardships can perhaps be attributed to the fortitude and grit that has led Ibaka to becoming a world-class athlete. After the war was officially declared over, Ibaka was able to focus on pursuing his dream. He would go on to play in a local club team, called Avenir du Rail, before being scouted after his performance at the 2006 U18 African Championships in Durban, South Africa. Doors would open, and Ibaka would leave his support system in the Congo to play as a professional in Europe, eventually solidifying himself as an NBA player — the first to hail from the Republic of Congo — in Oklahoma, and then in Toronto, where he resides today.

Ujiri and Ibaka’s stories show that basketball — and in a broader sense, sports — can have an incredible impact that surpasses any court or field. If there was any doubt about this, one only needs to look at politics to get a clearer picture.

GETTING WOKE

Sports can heal communities. It can mend rifts, strengthen bonds, and cultivate camaraderie; its power to unite a people is undeniable.

“[Sports] unites everyone involved towards a common purpose. Just like music, it’s something that makes people happy,” says Ujiri. “On the court, field, or wherever the playground is, it reveals the true impact of human interaction and affects everyone watching.”

But sometimes, in order to heal something, you have to break it. Such is the case of the sporting world’s attitude towards the socially-conscious athlete. Where once, an act of political protest would be considered a surefire way for athletes to exile themselves from the industry (and of their careers), perspectives towards the ‘woke’ sportsperson, general manager, or owner have started to change.

History provides a longstanding record that showcases this evolution well. The Olympic Games, often regarded as an arena free of politics, have been ground zero for some of the most memorable acts of protest in sporting history. Arguably the best known of the bunch occurred during the 1968 Mexico City Games. Tension was already at an all-time high as society collectively grieved over the tragedies of the ongoing Vietnam War and assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. On the podium, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two American athletes who had won gold and bronze in the 200 meters, famously raised their gloved fists during ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ as a symbolic protest against the oppression of the black community. For violating the Olympic charter, the two athletes were suspended from Team USA and told to pack their bags, receiving death threats upon returning home. A lesser-known story is that of their podium mate and silver medallist, Peter Norman. In his show of solidarity for Smith and Carlos, the white Australian would become ostracized in his home country, effectively ending his career in competitive athletics, despite being faster than any of his contemporaries.

And then there’s Muhammad Ali. Society often has a short-term memory when it comes to matters that conflict against the image of our idols. People forget that before he was universally celebrated as one of the world’s greatest athletes, Ali was shunned for refusing to go to war in Vietnam. More than that, he was sentenced to five years in prison, had his license to box suspended, and was stripped of his championship title.

He famously stated, “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs? … I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs. We’ve been in jail for four hundred years.”

Since then, attitudes towards the ‘woke’ athlete have inched forward. Not by a lot — because the risks are still high — but enough, at least, to notice that the tides have started to change. The conscious sportsperson now carefully treads a fine line between becoming the pariah of yesterday and being the vanguard of a new generation of socially aware athletes and fans, further displaying the bond between sports and the community at large.

In 2016, NFL star Colin Kaepernick (formerly of the San Francisco 49ers, and now a free agent) made headlines after he decided not to stand during the US national anthem as a form of protest against police violence towards people of colour, especially those in the black community.

News of Kaepernick’s defiance would eventually trickle up to president Donald Trump, who criticized NFL team owners by saying, “Get that son of a bitch off the field right now, he’s fired. He’s fired!”

Similar to Ali, Kaepernick’s act of rebellion drew the ire of many and would shut him out of his career at the peak of his talents. But it would also rally others in support and solidarity of his actions. The #TakeAKnee movement would strike a chord with other football players, eventually crossing over to other sports leagues.

While NBA Commissioner, Adam Silver, stated his expectations of the players to stand during the anthem, the league has yet to issue any reprimands for athletes who have raised their voices in support of Kaepernick’s movement, and in a larger way, become activists, themselves.

Bay Street Bull Masai Ujiri Serge Ibaka Donald Trump.jpg

Golden State Warriors star, Stephen Curry, refused to visit the White House in 2017, a tradition upheld by all professional sports teams after winning a championship. His sentiments were backed by other key members of his team, eventually drumming up the furor of Trump, who later rescinded the invitation in one of his signature tweets. Other athletes would weigh in on the matter, including goliaths of the sport, like Kobe Bryant, Chris Paul, and Michael Jordan. Most notable of those who supported Curry was his on-court rival, LeBron James, who would go on to state that the White House tradition was only an honour until the latest Commander-in-Chief moved in and defiled everything it stood for.

“THERE IS NO PLACE FOR RACISM IN SPORTS. THERE ARE NO SONS OF BITCHES IN SPORTS. THERE ARE JUST THE SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF OUR COMMUNITIES WHO HAVE COME TOGETHER TO PLAY”

It’s a point of contention for Ujiri, who vehemently opposes the thought of using sports to stoke the fires of prejudice and racism. “There is no place for racism in sports. There are no sons of bitches in sports. There are just the sons and daughters of our communities who have come together to play. As leaders, when we tackle these issues, we should show unity and focus on building harmony.” And boy, has there been unity — a communion of individuals ranging from the upper echelons of the league down to the fans, who have rallied together in support of the standards that sports should represent in the cultural dialogue.

“By acting and not going,” stated Curry, “hopefully that will inspire some change when it comes to what we tolerate in this country and what is accepted and what we turn a blind eye to.”

Later, the NBA Players Association would release its own statement, adding that it, “defends its members’ exercise of their free speech rights against those who would seek to stifle them. The celebration of free expression – not condemnation – is what truly makes America great.”

All of this has gone to show that, yes, the game is important — incredibly, unquestionably, absolutely important. But these events reveal that there is something that transcends it — the bigger picture.

Such notions circle back to Ujiri’s thoughts on the matter. He maintains that the responsibility of a sportsperson (or general manager, for that matter) goes beyond courtside displays or social media chirps.

“The bigger question is, ‘what are we doing in our own communities? How are we affecting change?’ At the end of the day, we can use that spotlight to make comments or protest, but it comes down to what we are doing in our local communities.”

He goes on, “That’s why I loved the comments from LeBron, Curry, Kobe, Lowry, etc. because, when you look deeper… they aren’t just talking, they’re living their legacy through their actions and changing the lives of others.”

Sports has, and always will, be a powerful platform to deliver a message and establish values in the community. And that’s exactly what Ujiri and Ibaka are trying to do within theirs.

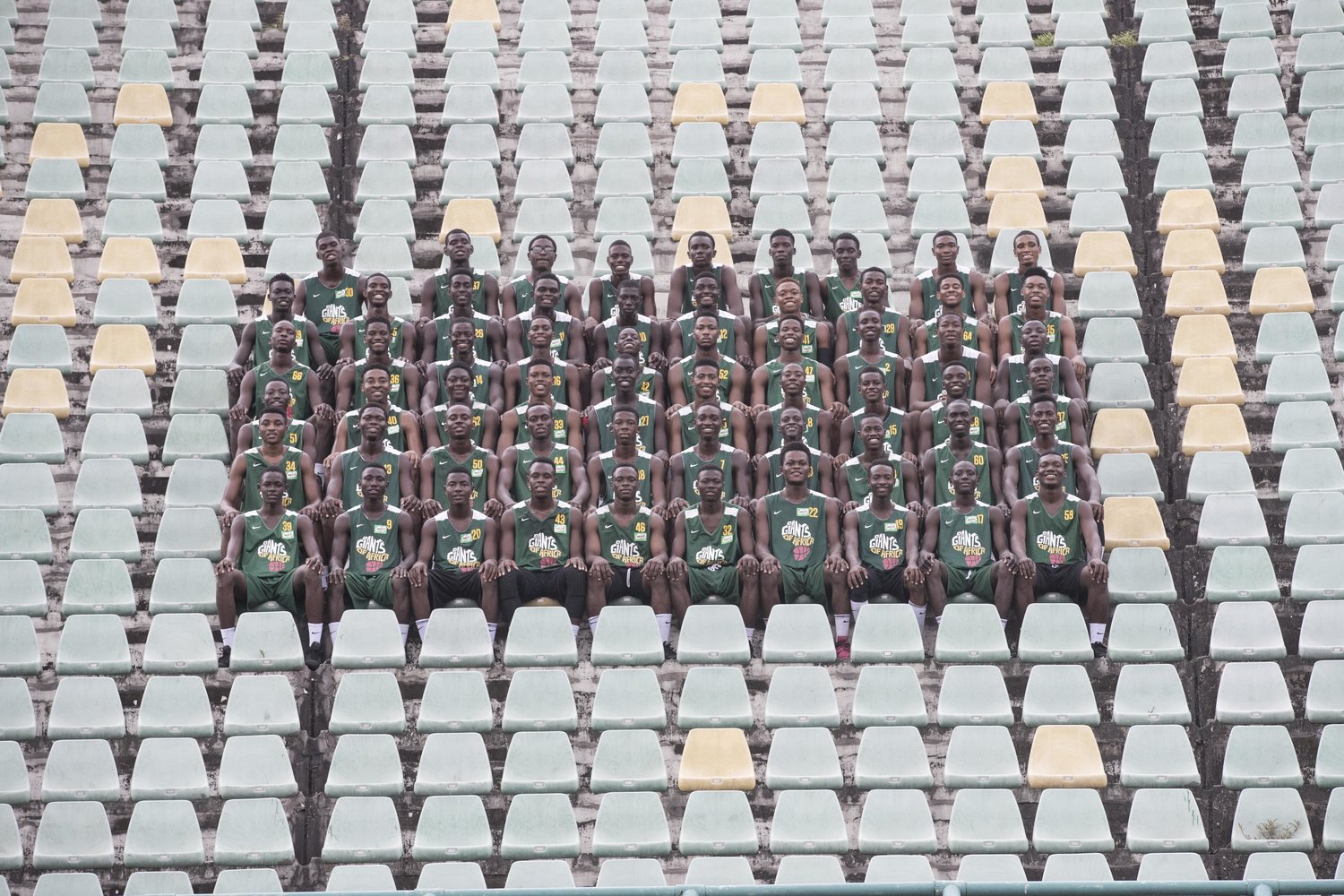

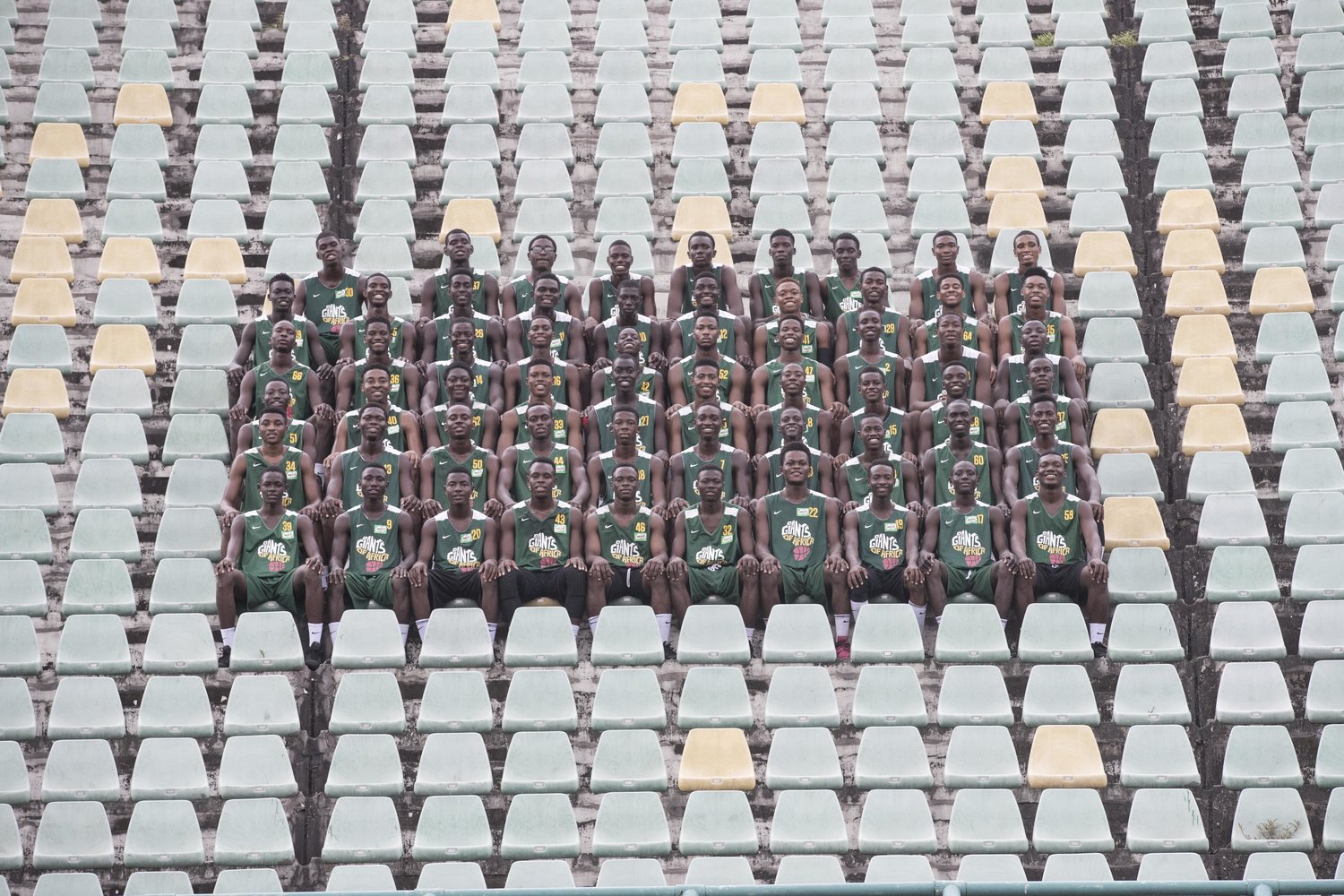

Photo: KevinCouliau

A GIANT OF AFRICA

When he joined as the general manager of the Toronto Raptors in 2013, Ujiri made history by becoming the first man of African descent to hold the position in any North American sports team. It was a big deal. Not just for the industry, but for the countless number of sports fans in the African community.

But the 47-year-old is quick to remark that having such a legacy doesn’t mean anything if it doesn’t open doors for those that come after him.

“What does it mean? If there is no second or third [African general manager] – if I end up being the only one – it’s a complete failure.”

Therein lies the sense of duty that Ujiri has always felt towards his homeland. For him, the most important work that he has done hasn’t been managing a roster of elite players, but rather, bridging the NBA to Africa to empower the youth through the sport.

Ten years before he assumed his current position, Ujiri launched his charity, Giants of Africa (GOA), in Nigeria. Back then, he was a scout for the Denver Nuggets and routinely came across a wealth of talent waiting to be discovered and nurtured.

Photo: Jamal Burger

A non-profit, GOA is a basketball camp that provides a safe place for underprivileged children and young adults by giving them access to proper facilities and coaching expertise. Above that, it also gives coaches and athletes an opportunity to get involved and serve as role models for others in the league. Since its founding, the organization has grown from a single camp in Nigeria to include three more countries in the continent: Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda.

While GOA functions as a summer youth camp, Ujiri’s intent has always been to use the sport as a vehicle to create lasting change and big dreams, all while cultivating the game in Africa. He recognized that the same principles that a sportsperson bears — those of respect, integrity, and honour — should carry through off the court as well. In his view, they are the traits that help shape a young mind into a change maker, which is why the skills that they teach outside of footwork and shooting, include more qualitative lessons that emphasize good values and leadership.

“[It’s] about life skills. We asked ourselves, ‘How do you shape a 17- or 18-year-old? How do teach them to be honest? To respect women? To be on time?’ I think these are things that are very important and often forgotten by people in this day and age.”

Photo: Jamal Burger

Photo: Jamal Burger

The reality of the matter, however, is that not every camp attendee will go on to play professionally. Not every child will be like Ibaka, have a 6’11 wingspan, or make it into the league – those instances are rare. So where do these kids go instead?

“We started teaching [the kids] the things that you can do outside of playing. If you play with a passion, then how do you channel that passion into something niche, like sports journalism, coaching, or sports medicine? We challenge them to expand their minds.”

“You don’t have to be an NBA player to make a difference.”

THE SON OF THE CONGO

No stranger to philanthropy either, Ibaka has also been hard at work to foster change in the communities back home.

Growing up in the Republic of Congo provided a host of challenges that he often found himself having to navigate as a young child. With no food, running water, or electricity at times, and under the veil of war, Ibaka’s reality provided but a small snapshot of what countless children experienced at the time. It is those experiences and hardships that bring the 28-year-old back to Africa every year. But more than that, and similar to Ujiri, it is the potential to build brighter futures that drives him the most.

“Not every kid is going to get into the NBA. I want to help by giving them a better education and resources, something that I didn’t have. I don’t care if you become a basketball star. My job is to give them the opportunity to have a better future. If I can do that, I’m happy,” says Ibaka.

Photo: The Serge Ibaka Foundation

His organization, The Serge Ibaka Foundation, was created to sustainably improve the lives of the youth in the Congo, especially in his hometown, Brazzaville, which boasts a population of approximately 1.8 million people. By partnering with established organizations aligned with the same vision, the Foundation has made strides in areas where help is needed most, such as children’s health, education, and nutrition.

For instance, working with the Starkey Hearing Foundation. An organization dedicated to providing hearing aids for those in need, Starkey Hearing worked alongside the Serge Ibaka Foundation to tackle the deafness epidemic in the Congo, allowing children to hear for the first time in their lives.

“That day I almost cried,” Ibaka said at a charity gala, remembering the effect that the experience had on him as he witnessed lives being changed.

In 2009, the Serge Ibaka Foundation ignited its relationship with UNICEF, and focused on helping street kids – those without any parents or family – in the Congo. Growing up with 17 siblings, the wellbeing of these children hit close to home for Ibaka. His family was instrumental as a support system growing up, and if he could be the same for these kids, by providing mentorship and improving their education and living conditions, they would be allowed to dream once again, or for the very first time.

Photo: The Serge Ibaka Foundation

Recognizing his efforts, the National Basketball Players’ Association (NBPA) brought Ibaka onto their Board of Directors in 2017 to serve as a positive example for others in the league.

“Serge’s insights and his accomplishments in international charity and philanthropy complement the wide-ranging work being done by our board president, Chris Paul, and vice president, LeBron James,” said NBPA Executive Director, Sherrie Deans. “With Chris, LeBron, and Serge on our board, we have an even stronger team to help us support and develop the charitable work of our players in the US and around the world.

Ibaka’s love for basketball is undeniable. You don’t achieve what he has, regardless of height or wingspan, without pure dedication to the sport. But beyond the court, Ibaka’s true passion lies in emboldening the children of Africa. The career of an athlete is short-lived, but philanthropy is a lifelong endeavour.

“One day I’m going to be 40 and stop playing basketball,” Ibaka said at a charity gala in Oklahoma. “But I want to keep doing this until my last day.”

“AFRICA MUST WIN”

Enriching communities has been a virtue of Ujiri and Ibaka’s as they have both ascended to the top of the sporting world.

For Ujiri, as the first GM of African descent in the league, and Ibaka, the first NBA player from the Republic of Congo, the responsibility that they bear is not lost on them. An entire continent regards the two individuals with awe and admiration, living proof that anything is achievable, no matter where you come from.

“WE’VE BEEN PUT IN THIS POSITION TO LIFT A WHOLE CONTINENT. WE CARRY AFRICA ON OUR SHOULDERS. THIS IS OUR RESPONSIBILITY. WE MUST WIN. AFRICA MUST WIN.”

Such responsibilities are ones that both individuals wear with furious pride. They embrace a mindset not weighed down by burden, but rather, lifted by the opportunity to impact change.

“We’ve been put in this position to lift a whole continent,” says Ujiri, sitting straight, eyes lighting up. “We carry Africa on our shoulders. This is our responsibility. We must win. Africa must win. We have to figure it out, and that’s by creating opportunity.”

Ibaka is quick to agree. “To me, it’s not an obligation. I have no choice. [Africa] is where I come from. I know how hard it is. I used to be one of those kids. I know.”

Ujiri continues, “We have to teach Africans to do better because they are great people. They are smart people. And where we can teach, we teach. [That] starts with the youth.”

“If you can teach [the younger generation] that they can change a continent, then they will be able to change the world.”

___

In an era where athletes yield more power and influence than ever before, and where social issues are again front and centre in the athletic arena, Ujiri and Ibaka have led the way by showing that we can always do more; that those in power have a responsibility to those who are powerless.

“Your job as a leader is to go and do better. And to teach people to do better,” says Ujiri.

They have confirmed what we have always known: that sports have never been solely about sports. They have been about lifting each other up when we are down, uniting one another, and acting as a team – a community – to ensure that everyone is taken care of.

The game may be basketball, but the endgame is bigger than that. It’s the ability to change lives.

VIDEO: Go behind-the-scenes on set with Masai Ujiri and Serge Ibaka and watch how it all came together.

Interview: David King

Words: Lance Chung

Photographers: Shalan and Paul

Stylist: Sharad Mohan

Hair and makeup: Demi Valentine

Stylist assistant: Carlo Alfonso Pacheco