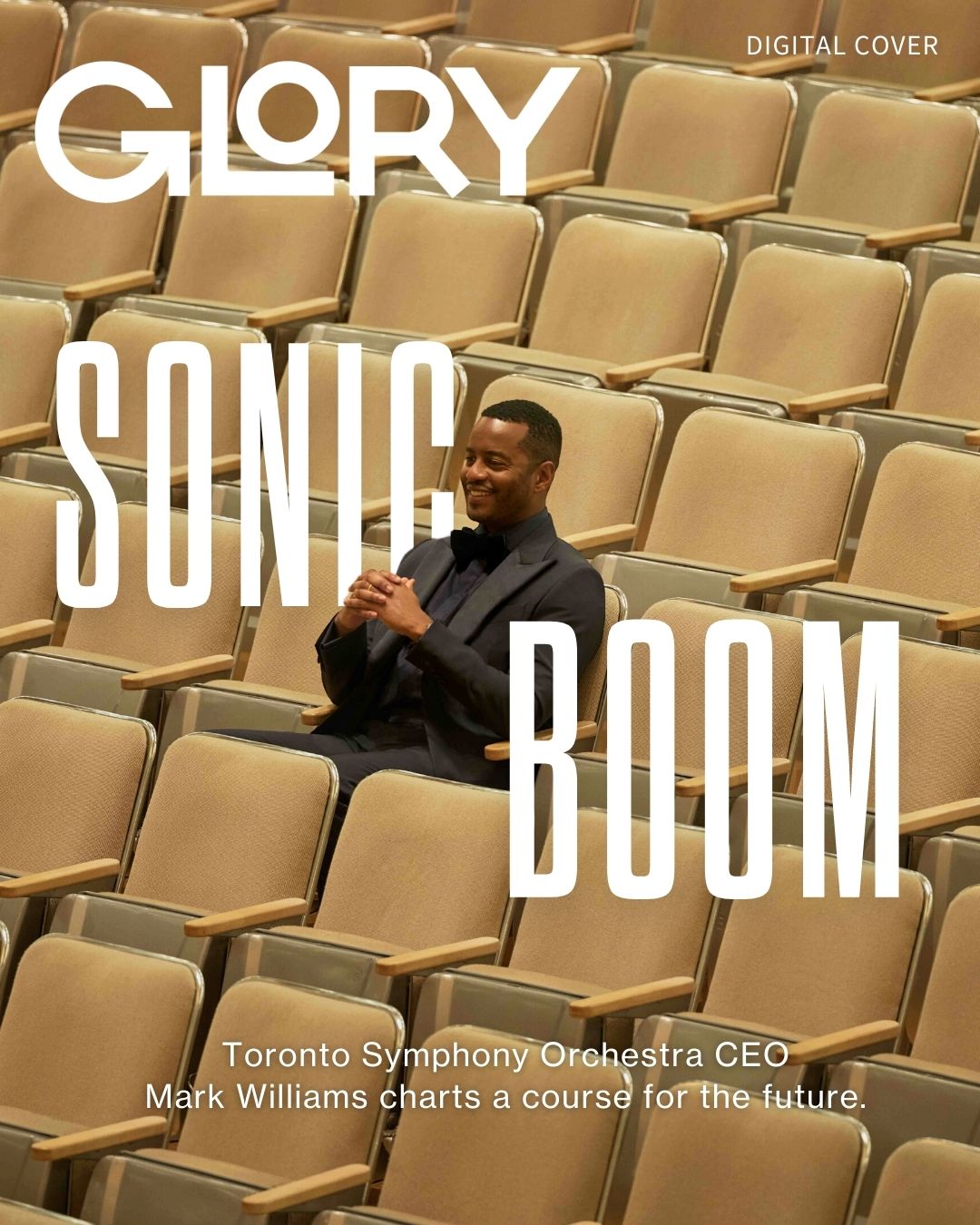

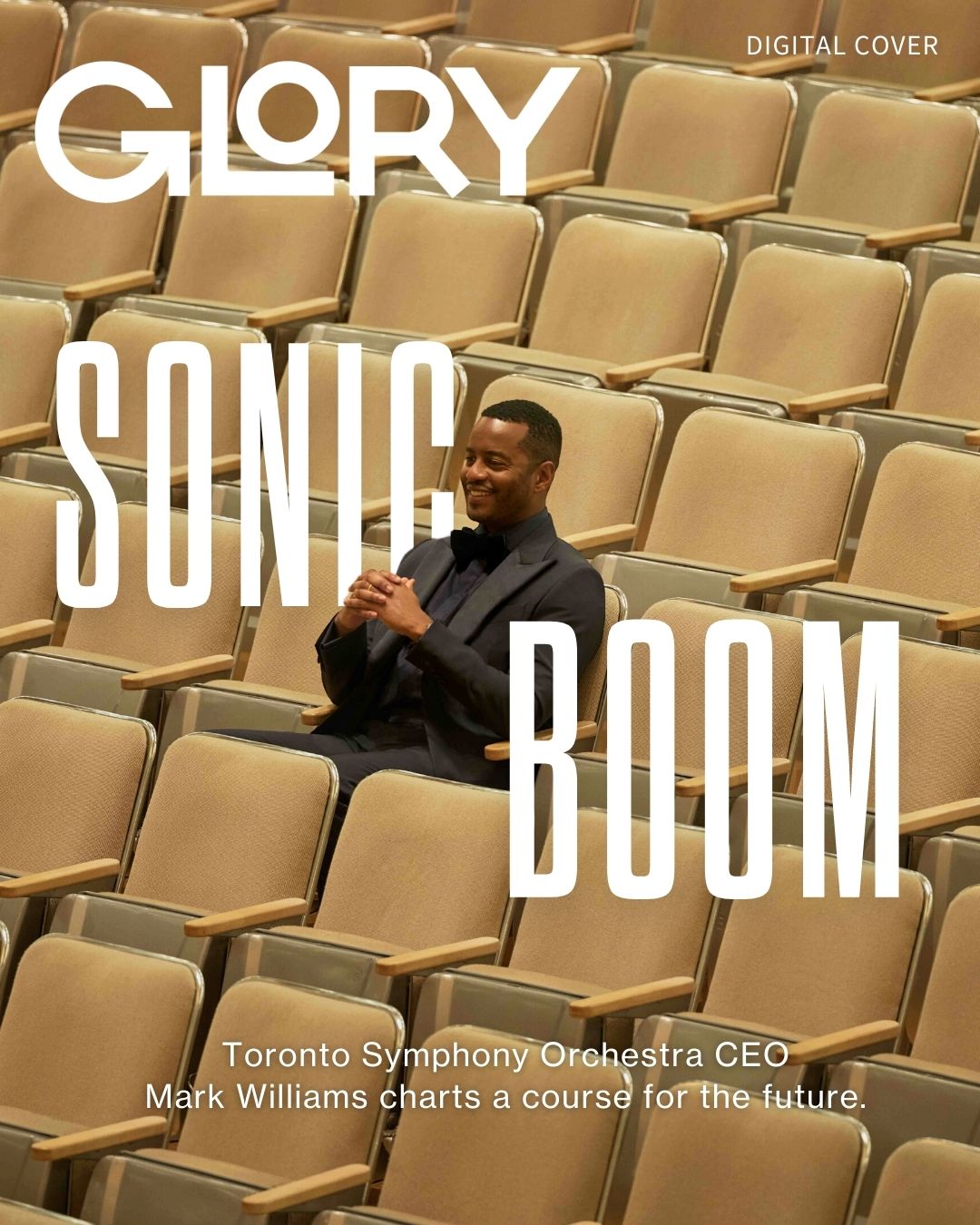

In a world that is increasingly becoming defined by technological advancements and endless content scrolling, what role does a symphony orchestra play in the big picture of it all? It’s a question that Mark Williams has had to confront in his role as CEO of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (TSO).

The challenge ahead is an interesting one—how do you honour the rich legacy of a century-old cultural institution without being beholden to that same history, to innovate, push boundaries, and charge into the future?

For Williams—the first Black CEO of a major North American orchestra—it’s about community. An orchestra is hardly a relic of the past but rather a dynamic force that has the power to open doors and minds by bringing people together, whether on the stage or in the audience.

As the TSO embarks on its 101st year and its next century ahead, Williams envisions an orchestra that listens more than it speaks, touching lives in ways that go beyond the concert hall.

For GLORY, Editor-in-Chief Lance Chung chats with Williams in his exclusive cover story about the power of music, diversity in the symphony orchestra, and what the orchestra of the future looks like.

Listen to the full interview on the Mission Critical podcast or read below.

If you stopped someone on the street in Toronto, what do you think is the first thing they would say about the Toronto Symphony Orchestra?

Mark Williams: I would say that most people, when asked about the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, would probably react to their perception of the art form more than the institution because I think the art form, itself, has created a kind of distance from the population. It has created a barrier for people to even engage with the institution over many years.

We’ve been working on bringing the orchestra’s presence more into the centre of everyday life [by] creating opportunities for people from all different kinds of backgrounds, from all different geographic areas to engage with the Toronto Symphony.

I’ll give you an example. For the past two years, we’ve started our season the same week that we do our big opening night concerts with a free open house and community concert. The hall is open for four hours and there are musicians and artisans from all over our community, from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds. What I like is that it’s not just providing a great afternoon out for people or their families, but it’s creating familiarity and belonging so they know that the Roy Thomson Hall and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra belong to them.

Are there any misconceptions about the orchestra that you hope to dispel through your work?

Mark Williams: There are misconceptions about who orchestral music is for, who it’s written by, who plays it, who programs and produces it.

One of the things that has been so interesting about my career is, I’m a six-foot, two-hundred-pound Black man. But I’m also the CEO of a major orchestra. I believe that my very presence challenges the idea of who classical music or orchestral music is for. I do this, certainly not because I love the stress, but because I love this music and making music with others. It has changed my life.

Going back to your French Horn days, what made you fall in love with music and the business of music?

Mark Williams: I’ve thought about this a lot over the years and I’ve frequently believed music itself was the reason I fell in love with it but it wasn’t that. Playing music was the first time I truly felt I belonged somewhere, surrounded by a community of people.

Secondary to that was the ability to express what I couldn’t yet say. I started doing this seriously when I was a teenager and I didn’t have the emotional maturity to say some of the things that I needed to say, but I could do it through my horn.

What I feel when I’m working at the very best and highest level in the music business is there’s no other talent or skill that I have that could make a greater impact on the world or bring more joy and meaning to more people. That is the greatest feeling in the world.

In what ways do you think the symphony orchestra acts as a reflection of its time, especially when so much of the programming and material is a product of eras past?

Mark Williams: I don’t believe that a symphony orchestra is a museum piece. Although we might be playing music that was written 400 years ago but the way that we, as an audience and musicians, see it is always through a contemporary lens.

Beethoven wrote his Symphony No. 3, his Eroica symphony, and was going to dedicate it to Napoleon. But then Napoleon crowned himself emperor and Beethoven crossed [his name] out and, instead, dedicated it to Eroica, a hero. The reason that the piece matters today is not just because of the notes or because it’s pretty. It matters because we’re still struggling with people who abuse their power, with people who believe that they are above the law, that they are above humanity, and above the people that they’re meant to lead.

These pieces that have come down to us through the years survive because they still have relevance, speak to the human condition, and because we can see ourselves in them if they’re well presented.

The other part of why we’re not a museum piece is that we commission so much new music. In any given year, we play 20 to 25 pieces that have never been played before.

And those could be from international artists or Canadians. So, there is always a dialogue between modern sensibilities, what antiquity has to tell us, and how the actual problems of today are rendered through music.

A big theme in your program book messages last year focused on opening doors, literally and figuratively. Talking about opening doors would imply that they’ve been closed at some point. In the orchestral world, which barriers have historically blocked access to the art form, whether as a participant or as a consumer of the art?

Mark Williams: Many barriers exist, and they are not unique to orchestral music. It’s education, cost, location, transportation. It’s that very important piece of belonging, right? Will some people look like me? Will I feel welcome? Will I be ostracized?

Those have been very real barriers in our industry. It probably sounds pessimistic to speak about it in this way, but I don’t think that we will ever overcome those barriers if we don’t look them in the face, admit where, as an industry, we could be better, and start dismantling them.

I would say the last piece is representation and being seen in the programming. Seeing that music by artists and people who look like me and come from where I come from is making an impact in the industry. That makes a huge difference.

You are the first Black person to run a major North American orchestra. In so many ways, that is such an incredible achievement and in other ways, one can’t help but ask why it’s taken so long for such a milestone to be passed. Did you realize the weight and significance of your appointment when you accepted the position of CEO at the Toronto Symphony Orchestra?

Mark Williams: One never fully realizes the weight. You know it intellectually but you don’t know it emotionally. The emotional piece hit later and it wasn’t pretty. It makes me deeply sad because I’m not the first person who’s wanted it. I’m not the first person who’s been qualified for it. I’m not the first person who could have really done a great job and made a difference but somehow, I’m the person in the seat and I don’t know why. It dictates the work because I may be the first but I can’t be the last. I have a real responsibility to drop that ladder behind me.

RELATED: Can Brandon Gonez Give You a Reason to Trust the News Again?

What advice do you have for other people of colour or minority communities when it comes to taking up space and making your presence known?

Mark Williams: You know, it’s so funny. I oddly feel not very unqualified to answer that question because, for the most part, I’ve approached my career by just doing really good work. But I know that’s not enough. The representation of people of colour in so many fields is low not because they’re not doing good work and they’re not working hard, right? There are systemic issues.

One of the things that I would say is, we all need to focus on helping each other and that’s not just people of colour. It’s all stacking hands on the fact that our industries will be better when they’re diverse. Diversity is excellence. You will be more excellent if you are more diverse, if you have that diversity of skills, perspectives, and whatnot.

I think back on my career and the number of people who helped me all along the way. I had people who saw talent, determination, and desire, and they helped even when I didn’t think I needed it. Sometimes, when I didn’t want it.

What is a moment in your career where you felt like you had really given someone visibility and made them feel seen?

Mark Williams: Before I was the chief executive, I was a programmer. Every day I was making decisions about who’s on that stage and what are they playing. Every day I felt like I was making decisions that would help make people visible and make their stories visible. That was, one of the exciting parts about the job.

TSO also has a program that provides access to the neurodiverse community.

Mark Williams: We have a program of concerts that we call Relaxed Performances. If you think about orchestral music or classical music of any kind, it’s like a painting that is done on a canvas of silence. That silence is an important part of what we do, but it’s also a barrier to certain people. So, what happens if you want to hear a concert but you cannot be silent? Or you need to move, which creates noise. There is an environment where you’re not welcome or where you can’t access the product. The conductor will walk out on stage and say, OK, this is a relaxed performance and whatever you need to do to enjoy this experience, to be able to engage with what we’re offering you today, please do so. We have a quiet room if it becomes too much for you, we have ear plugs and noise-dampening headsets, and we have fidget spinners. If you need to vocalize, you can do that. The point is, whatever it is you need to do to enjoy this experience, you can do it. You’re safe here and you’re welcome here.

What I heard as I walked around the hall and talked to people, the story that I heard over and over was that this [experience] was something that had previously not been available to these families. Or, if you are a caregiver and there’s no one else to care for your loved one, and you like music, you can’t go. Suddenly we’ve created this opportunity where whole families can come and experience the orchestra together. I found it incredibly moving and just a reminder of why we’re here.

I went backstage and I was talking to some members of the orchestra, doing an informal poll by asking what it was like for them. It was Beethoven Five, which is not an easy piece, and there was noise in the hall. One person said, “It’s worth it. We work harder.” I asked why. “Because this audience deserves the very best of what we do.”

That’s what gets me out of bed in the morning.

TSO recently celebrated its centennial last year. What gives you hope as the orchestra enters its next 100 years?

Mark Williams: What gives me hope, frankly, is that this is an organization located in a city, neither of which has become what they’re going to be. It’s so interesting for me to live in a city that is still very young and trying to figure out what it wants to be and what it cares about. That is incredibly exciting.

I feel that this orchestra is very much the same. It’s an orchestra that is 101 years old now and has a rich, long, and deep history. And yet, it’s an organization that I think holds that history so lightly. That is the very best combination because there’s the kind of stability and gravitas that a century brings, but also the curiosity and openness about the future.

If the goal of an orchestra is to be a tool and a servant of its population, you need a very flexible orchestra to be successful in this city. We have one and that’s why I’m so thrilled about the next 100 years.

We live in a time that is defined by fast consumption, immediate gratification, infinite access to any kind of content, and automation through technology, especially of the creative fields. With all that in mind, what do you think the orchestra of the future looks like?

Mark Williams: I think the orchestra of the future is an orchestra which expands who it’s for—an orchestra of the future is one that really thinks about a kind of programming that touches a wide variety of communities. The future is an orchestra that is listening more than it’s speaking.

For example, 40,000 young people per year engage with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s education programs. Some of them are through concerts, workshops, our youth orchestra, making music, and being coached by our musicians. That comes about by listening and asking a community what it needs. We go into care homes and we work with seniors who have dementia. We’ve given somewhere around 350 of these concerts to date to seniors who are isolated and were especially so during the pandemic when this program started. We can bring connection and joy.

There was this gentleman who sang throughout the entire performance and afterward, his caregiver told us that he was non-verbal. She hadn’t heard his voice in years, but music activates a different part of the brain than speech does. I just thought that was incredible.

So, I think an orchestra of the future will serve their community in ways that are quite different than just coming to the concert hall, hearing a performance of Beethoven, and going home.

In many ways, you are also a maestro of the many moving parts of your organization. How would you describe your leadership style?

Mark Williams: It’s interesting what I might say and what my team might say [laughs]. I try to always remember that being a leader and being the CEO of a company of this size does not mean that it’s all on your shoulders. It’s really easy to get into a version of just doing things yourself. It does not work. I like to focus on listening as much as possible and trying to share the big picture so that my team knows what I value. In an ideal world, those values link up with the values of the organization.

What have you learned about yourself as you’ve led the TSO that you weren’t aware of going into the position?

Mark Williams: Leadership is all about self-discovery because if you don’t understand yourself, you don’t understand others. I think I’d like to say—and I’m not fully there yet—that in my time at the TSO I’ve learned how important compassion is and that starts at home. If you are not understanding with yourself, it’s impossible to turn that out into the world.

I’m a very driven person. I have a background in performance, which is quite exacting. I got pretty far in my career before realizing that I’m kind of a nasty bully with myself and I don’t accept failure. I hold myself to an incredibly high standard and sometimes that seeps out into other people. I think in my time here, I’ve started to learn that maybe I need to be a little bit more gentle with myself and that will help me be more gentle with others.

What would you say is your mission?

Mark Williams: My mission is to bring meaningful musical experiences to our community.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Listen to the full conversation between Lance and Mark on the Mission Critical podcast.