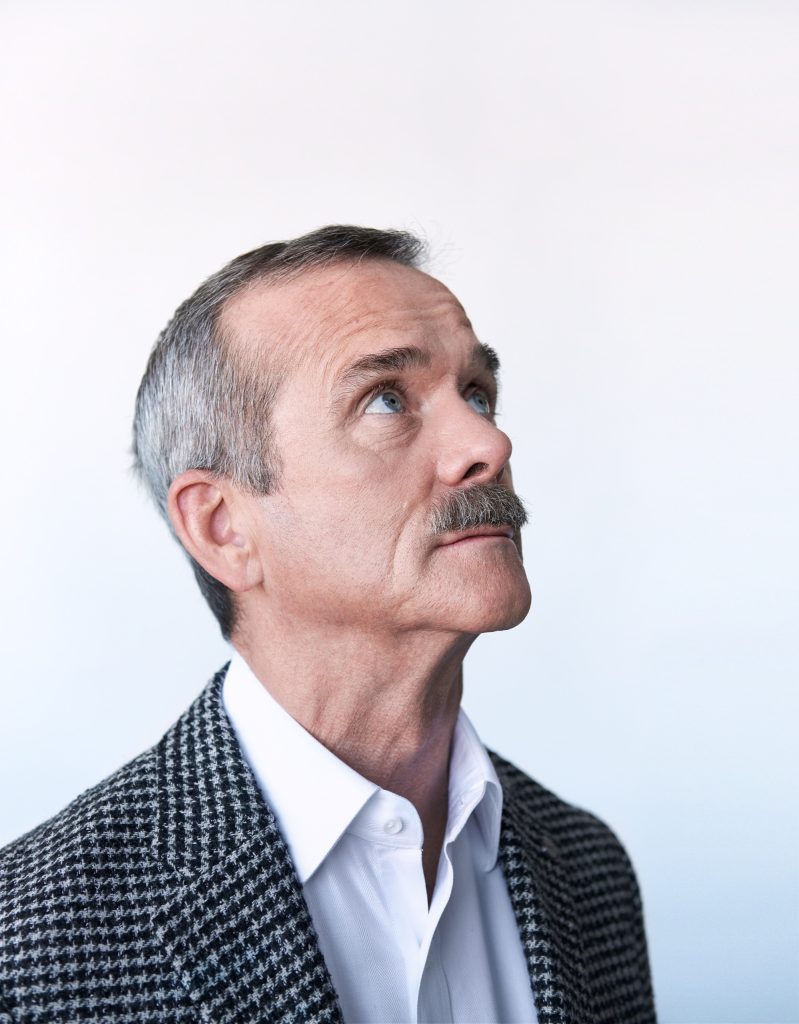

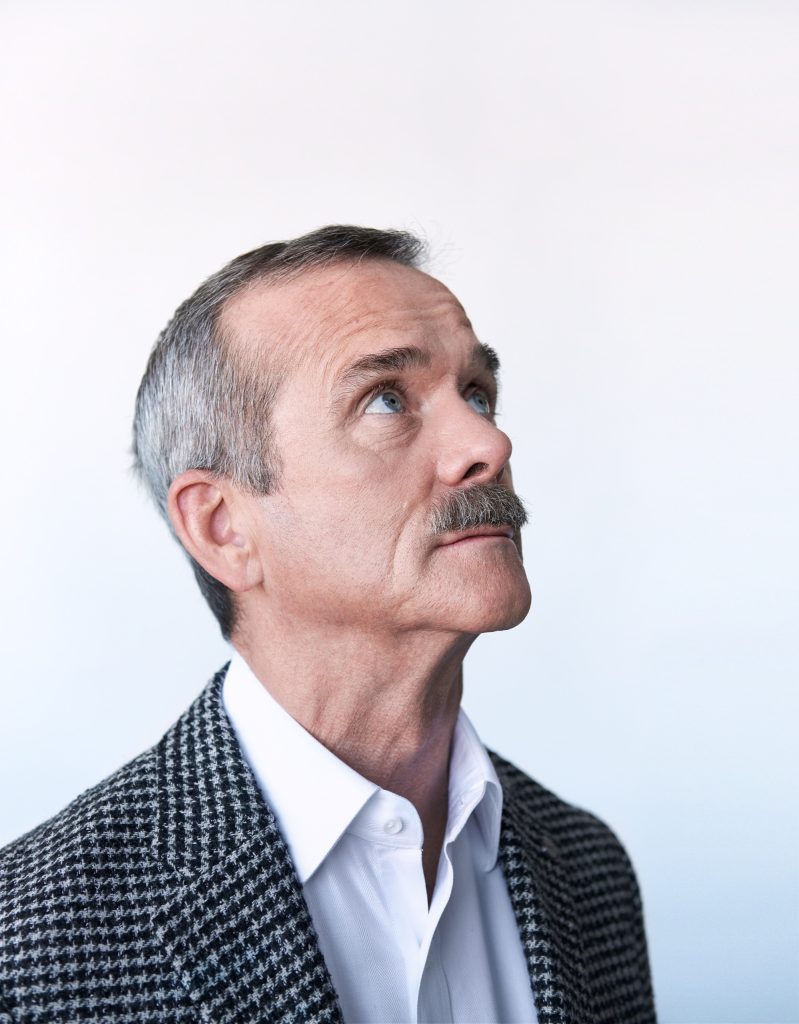

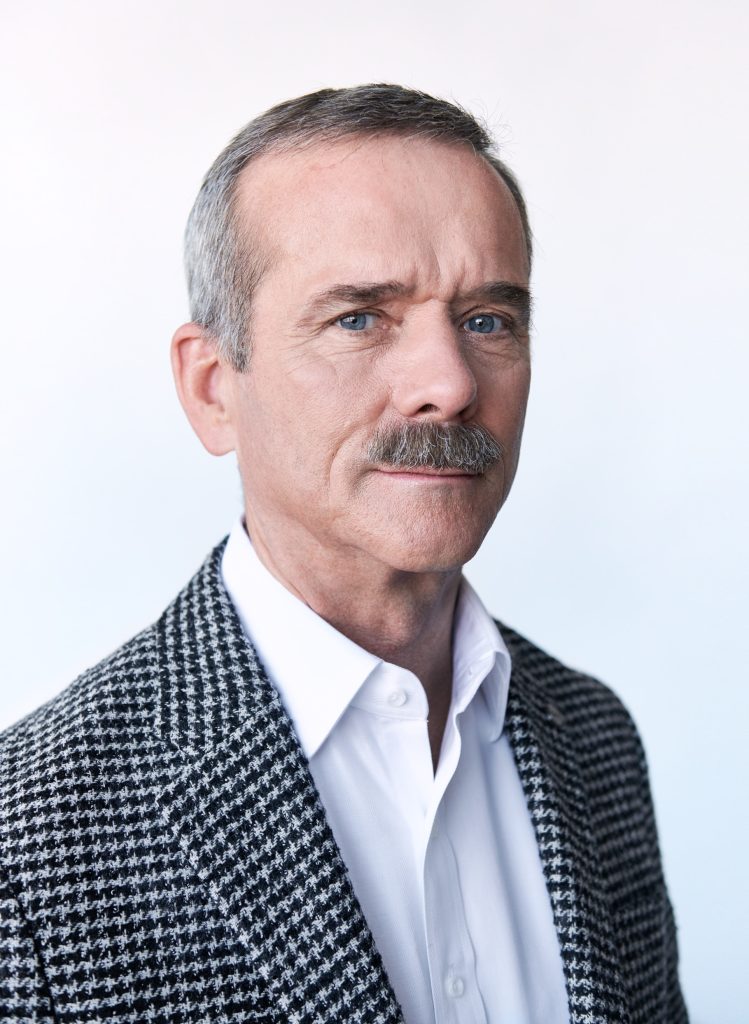

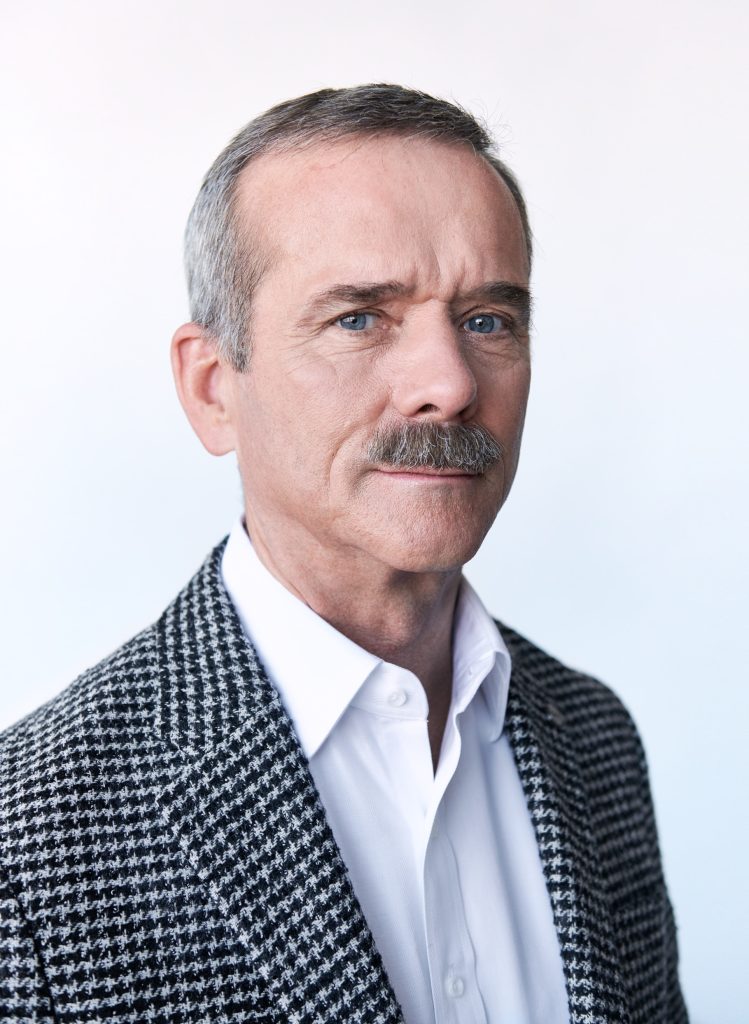

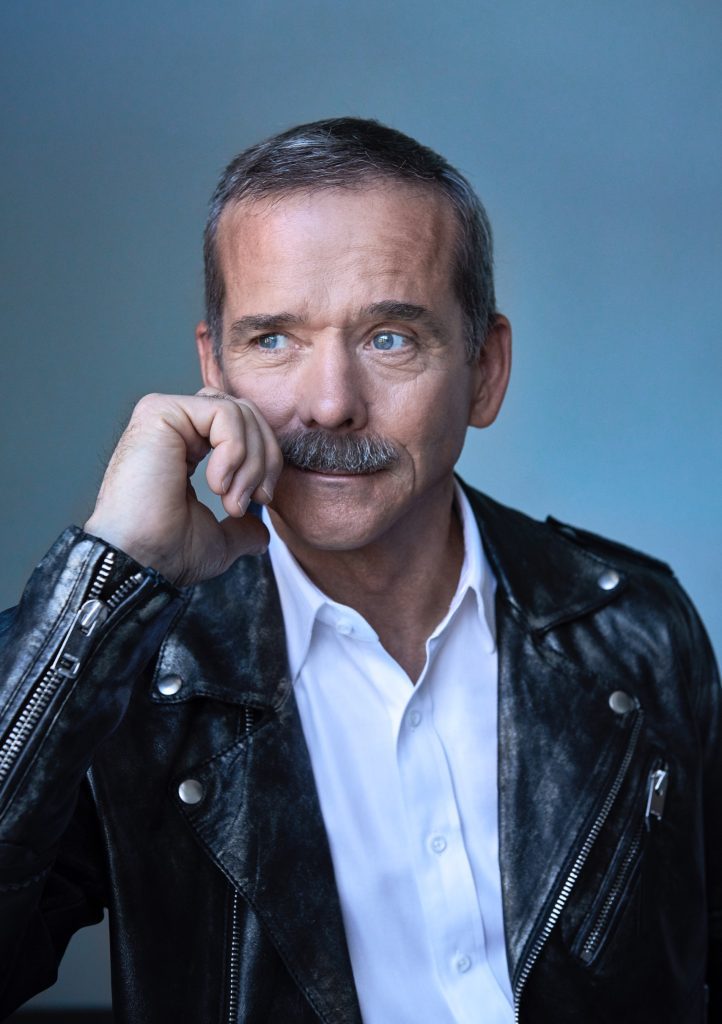

The first Canadian astronaut to walk in space reflects on his storied career and tells us why success is all about perspective.

Written by Chris Metler

Photography by Janick Laurent

Grooming by Antonio Hines

Picture humanity going back to zero. No electricity or semiconductor devices. No anesthesia or penicillin. No automobiles or airplanes. No telephone, radio, television, or Internet. Nothing.

There’d be almost no time to strive towards original thought. Building all it would take to enable us to really pursue what we’re interested in would prove too arduous. We’d barely survive.

It’s why, as far as Commander Chris Hadfield is concerned, the word ‘legacy’ amounts to a gift from the past. You see, we’ve been bequeathed these towering achievements and untold more by trailblazers who stretch back to a bygone era. The first Canadian to walk in space further deems both himself and us the beneficiaries of their pioneering work.

With this in mind, he figured his own legacy would one day indicate a person who got incredibly lucky. A heavily decorated astronaut, engineer, and pilot who sliced through the stratosphere on three separate occasions, Hadfield is the very grateful product of the legacy of everything accomplished over the course of yesteryear leading up to where we are right now.

Only, with his recent induction into Canada’s Walk of Fame giving way to inward introspection, Hadfield realizes there may be value in his triumphs enduring as neither singular nor ultimately transient.

Perhaps he can have a lasting impact. Maybe what he hands down to future generations can extend outside the expanse that exists beyond the Earth and between celestial bodies, or the spacecrafts that took him there.

NAVIGATING THE STARS

Qualify greatness however you please. Actually attaining it, however, tends to require an effort surpassing what is just necessary to stay the course. Look at any milestone moment in history, be it Galileo peering through a telescope and discovering that we’re not the centre of the universe, or the Wright brothers consummating man’s eternal quest to fly.

Hadfield acknowledges a common thread weaving society’s most remarkable accomplishments together: “Someone was dissatisfied with the status quo and tried to change things. They definitely pushed the comfort envelope.” For his part, he first glimpsed greatness at this lofty echelon on July 20,1969. Yes, the night the first man walked on the moon; when Neil Armstrong took one small step for a man and one giant leap for mankind into immortality.

Stepping out onto the pitch-black exterior of Earth’s only permanent natural satellite – studded with craters and strewn with sharp, angular regolith – Armstrong’s heart rate raced to 160 beats a minute. Young Hadfield’s wasn’t too far behind.

“Imagine if you were watching the X-Men and then, when you went outside the theatre, an actual X-Man went by. It would change your whole perspective of the thing, and also what it might mean for you – that this isn’t just pretend.”

Raised on a corn farm in Southwestern Ontario, he’d been a kid with a wild imagination, engrossed in the galactic genre films of the ‘50s and the mid-’60s debut of Star Trek. The lunar landing seized his science fiction world and suddenly grounded it in an authentic human event. His boyhood aspiration of launching into space was all of the sudden a possibility.

“It went from being fantasy, from Edgar Rice Burroughs and Arthur C. Clarke books, to a real choice that maybe this little kid could someday actually go do that. It shifted my whole perception of choices in my life,” he reminisces.

From that evening onwards, Hadfield oriented his life towards spaceflight. Faced with proverbial forks in the road along the way, he took whatever route could possibly move him closer to that grail.

THE VECTOR OF YOUR LIFE

When performing a spacewalk, the full, blistering force of the sun mercilessly beats down on one side of your body. There are no tiny air molecules to absorb its energy or provide a measure of relief. It is hotter than boiling water. And yet, on your other side, in the shade, it’s hundreds of degrees below zero.

Your “attitude” – astronaut-speak for the way you’re pointed – is super critical as to how your body will react to the temperature. In spaceflight, it’s fundamental for a favourable outcome. It could mean the difference between life and death.

It turns out, there isn’t a very giant leap to applying this logic to your whole life.

“The direction that you’re pointed, the deliberate ‘attitude’ that you have chosen, is going to really define the vector of your life, whether it’s mental or physical. It’s worth thinking about… because where you get to next is the direct result of the attitude you have right now.”

Hadfield subscribes to this rationale. If there is one thing that he can control, it’s the direction that he chooses to point himself on his journey, compelling him to consciously monitor and correct his orientation along the way.

TIME AND SPACE

When the OMEGA Speedmaster Professional X-33 debuted in 1998, it was touted as the watch at the forefront of a new millennium of space travel. After all, this was coming from the same brand that launched itself into the cosmos on the wrists of Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong when they famously wore the Speedmaster Professional (“Moonwatch”) and landed on the moon in 1969.

Almost 30 years later, OMEGA debuted the X-33 as a follow-up to its interstellar predecessor with improvements made to meet all criteria necessary for professional pilots and space travellers at the time. The analog-digital hybrid featured a quartz movement and is a particularly special timepiece for Chris Hadfield, having kept him company while he conducted his research (and serenaded the world) while aboard the ISS.

The dial and display were made as clear as possible with luminous hands and hour markers against a black background, along with a digital display with high-contrast LCD letters and numbers at the request of astronauts who often worked in low light environments. The titanium pushbuttons and crown were made to be easily manipulable by the heavy gloves worn by pilots and astronauts, and a double titanium caseback (complemented by a titanium bracelet) made it possible for the alarm to reach over 80 decibels, as required in space shuttles.

Designed to withstand extreme conditions, special care was taken to adhere to stringent technical specifications. Every function of the timepiece was purposeful — and many of these features continue to be replicated in subsequent timepieces by OMEGA as it builds on its iconic legacy written in the stars.

Upon being told it was improbable for any Canadian to make it to outer space – American and Russian astronauts having dominated space travel in that era – his attitude adjustment was that if they were all fighter pilots, then he’d better become one, too.

Joining the Air Cadets at 15 years old, he obtained his glider pilot license, then advanced through the Royal Military College, the Canadian Air Force, and a stint as a test pilot in the United States. He was later selected by NASA to become one of four new Canadian astronauts from a staggering field of 5,330 applicants.

Before rising to command of the International Space Station (ISS) and being given a five-month mission (he was the first Canadian and only the second non-Russian or non-American to be put in charge of a large-scale orbital crew) his attitude adjustment was to use this golden opportunity to gain a better understanding of certain issues that directly affect us on Earth.

Running no less than 130 experiments, most dealing with the impact of low gravity on human biology, he established a NASA record for science conducted on the largest orbiting laboratory in history.

And incidentally, way out on the very fringe of the human experience, Hadfield’s much-publicized decision to chronicle activity aboard a space station and post it on social media turned on its head public perception about what an astronaut’s life is.

It could be likened to yelling into the void – or standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon and shouting hello. Except sometimes the echo that comes back is a surprise. In his case, the reverberation was more like a resounding roar.

UNCHARTED TERRITORY

Hadfield is the most celebrated astronaut alive, widely held as the successor to Neil Armstrong, his hero and initial paragon of greatness. That always motivated him: standing on the shoulders of everyone who made what he did possible, then adding to that solid foundation for those who followed after him. If nothing else, the run he’s had has been privately rewarding.

“It’s so nice to be able to stand on the platform of the things that I’ve done and use that realistically, but also metaphorically, to look around. You can see further because of the platform that you’ve built underneath you. You can see more clearly. You can draw conclusions that were beyond your grasp earlier in life.”

And though he never became an astronaut to be famous – the aforementioned Walk of Fame honour proving somewhat ironic – he interprets his somehow tripping over the line of celebrity as external validation of doing the things that have always been deeply, personally important to him.

Still, Hadfield, who retired from the Canadian Space Agency after returning home from ISS in 2013, finds himself at a crossroads. After all, life comes in stages. And in the immediate wake of the Walk of Fame induction, he’s landed somewhere between the creating and reflecting, and sharing stages.

On one hand, he hasn’t lost sight of the kid who chased his boyhood aspiration then grew up to become a bona fide spaceman. He considers himself living proof of science fiction becoming “science fact,” as well as of the unfathomable becoming reality. On the other, he is now a seasoned jock that voyaged into the great unknown and came back an inspirational icon.

The question is: what do you do with your life’s experiences when you arrive at this particular juncture?

Here is a man who logged nearly 4,000 hours in outer space. Here is a man who has glanced right and seen our immense planet – the only astronomical object known to harbour life – as a little blue marble with white swirls, then glanced left and gazed into the largely empty clearance between the stars and galaxies.

Do you try to trade on that distinction or recapture lightning in a bottle? Do you somehow reconcile that you’re going to have interesting thoughts for the rest of your life, but are done sharing them? Do you allow yourself to get bored, isolated, and sedentary?

Maybe it’s none of the above. Instead, maybe there’s an opportunity to recognize the singular journey life has taken you on. To the degree where, if you’re up for the challenge, your ongoing objective shifts to packaging your unique vantage point in a manner that will prove useful to others.

THINK LIKE AN ASTRONAUT

A singular commitment to “thinking like an astronaut” – keeping your head in a crisis and improvising good solutions to tough problems when every second counts – afforded Hadfield the resources to make good on a lifetime of deep-rooted interstellar ambition. It furnished him with a different view of the world, both literally and metaphorically.

By promoting this same mindset across a multitude of outlets for anyone interested to take advantage of, he may be able to help earthbound humans achieve a similar level of prosperity and happiness in their lives. It’s mostly a matter of changing your perspective.

When he’s not booked for international speaking engagements or penning bestsellers like You Are Here: Around the World in 92 Minutes and An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, he’s sharing his knowledge of space in a new MasterClass video series, which is designed to aid future astronauts and space tourists with their own missions. And when he’s not sharing that knowledge, he can be found in the classroom of his alma mater, University of Waterloo, where he teaches aviation and helps with studies in the health sciences department. And when he’s not in that classroom, he is off mentoring Canadian Space Agency astronauts informally, despite his retirement. And repeat.

Hadfield’s meteoric trajectory, in a large sense, has been about taking those years spent in worst-possible-scenario training and embracing the importance of a “pessimistic view” to propel himself forward. According to him, blind optimism results in disappointment. While optimistic goals are fine observed through a pragmatic lens, it’s important to acknowledge that things can and will go wrong. As such, contingency plans are crucial and will help you better deal with what life throws at you. That’s the power of negative thinking, and ultimately the solution to tackling fear – something an astronaut would be well acquainted with.

“How do you not be afraid, or how do you deal with fear, is a worthwhile question to ask,” he says. “To me, it’s an indicator that I’m not prepared for what’s about to happen. If you [have that] rising panic feel and [you get] butterflies in your stomach, that’s your body telling you that you didn’t get ready for what’s about to happen.”

An expert in navigating the space outside of his comfort zone, Hadfield advocates that fear is ultimately the result of the unfamiliar. “Things aren’t scary. Sometimes people are just scared. We often confuse the two,“ he says. “[People] say, ‘Boy, isn’t flying a spaceship scary?’ The spaceship doesn’t care, [it’s] just a thing. The real question is, did you learn how to ride it properly so that you’re no longer afraid? To me the greatest antidote to fear is competence, and that’s what I always work on. There’s always time available. Get ready for the things that are liable to happen.”

These real, actionable insights comprise the bouquet of flowers that is Hadfield’s entire life. Pick out of it as you will; whatever helps you out.

MOVING THE SHIP FORWARD

Successful people rely on themselves. They don’t seek permission to do what they want and they certainly don’t allow others to slow them down by relying on them. They have belief and confidence in their ability to achieve their dreams.

Chris Hadfield wasn’t destined to be an astronaut. He had to turn himself into one. And if he had his druthers, it would be solely up to him whether he was judged to be successful or not. The same goes for whether he measured up to his earliest benchmarks of greatness.

When he reaches the end of the road and reminisces – sitting in his rocking chair at the old folks’ home, talking about how great he was when he was younger – Hadfield hopes some of the amazing things we’re eventually able to do will be the direct result of decisions he made during his own life.

Until then, he equates carrying the huge tranche of legacy he does to being an oarsman in a gigantic vessel, one that is never going to stop. How far will he be able to move the ship forward? Presumably right to the extreme limits of understanding and achievement in areas yet to be explored or developed.

To the final frontier – and beyond.