Today’s fastest-rising star of fashion design, Iris van Herpen, consistently surprises the world with her innovative haute couture collections. A relative newcomer who launched her label in 2007, the Dutch designer was described by Vogue as “fashion’s leading exponent of what technology can do and what it will mean for us.”

Written by Popi Bowman

Photos by Popi Bowman and courtesy of Philip Beesley

Van Herpen’s futuristic – or sometimes, she has said, “fossil-like” – fashions wouldn’t be possible without today’s technologies, especially 3-D printing and computational design. But there’s another force at work behind the scenes, and his name is Philip Beesley, a Toronto-based architect rooted in the arts and philosophy. Throughout the architectural universe, his name is fairly well-known, especially internationally; however, as Beesley admits, “Here at home, perhaps I’ve been a bit shy about it, but the recognition isn’t as strong for our work.”

Even so, Beesley is an accomplished creator, with an Ontario Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Architecture and the Prix de Rome for Architecture in 1995, along with numerous books and academic essays to his name. As a long-time professor and collaborator at the University of Waterloo’s School of Architecture, he was an early adopter of 3-D technology even before the school established Canada’s first educational digital fabrication facility almost 20 years ago.

Hylozoic Ground was a direct inspiration for Iris van Herpen’s Hybrid Holism haute couture show in 2012, which became the reason they met. After hearing about the collection, when Beesley contacted van Herpen, they found an instant rapport: “An afternoon conversation turned into many hours, and since then we have done 10 collections together,” he says. “We discovered a common vision – an instant friendship and understanding.”

Since then, Beesley’s interdisciplinary studio has played a growing role in bringing van Herpen’s wildest fashion imaginings to life. Now the self-described “shy” architect finds himself deeply embedded in, as he says, “this immensely self-conscious, extraordinarily social world of fashion.” Behind the scenes, as van Herpen refines her ideas for each collection on another continent, Beesley’s team in Toronto is developing new materials and techniques to push the envelope of what is possible in couture. “Right now we’re working on very, very thin, mechanically and thermally stretched meshes,” he explains, “and that’s working from a hybrid method that we’ve been developing with Iris together. One of the things that’s made that possible is a new, very large-bed, extraordinarily precise laser cutter that can move into metal cutting as well as polymers, and can do strand-based cutting akin almost to the density of weaving, and that’s combined with computational modeling.”

In some cases, Beesley explains, one garment may represent thousands of hours of crafting. A machine shop lives behind his studio wall, containing the massive laser cutting bed and a wall bedecked with hand tools. “In the cycles of back and forth with Iris, we’re working at the level of a little bit beyond the medieval guild, but not too far beyond – so you can think of where we’re sitting here, with all of these prototype materials around us and the shops behind us, as a kind of prototyping lab that comes just before industrial applications,” he says. Beesley’s studio directly manufactures some of the raw materials, “and then Iris’s atelier will assemble and extend them, in some cases outsourcing, using patterns that are shared.”

The development and design process is a constant back-and-forth, but rather than sounding tedious, Beesley’s description almost evokes children at play: “I was with Iris just a couple of weeks ago and we shared a couple of days, combinations of very quick exchanges where we unpack a box and spread it out and try things on and play, and then each person leaves with some new samples and ideas for pushing things further.” In the process, both have discovered new ideas that influence their work individually, from the scale of clothing to that of architecture. “The two bodies of work are really in very direct conversation back and forth,” Beesley explains. “The architectural orchestration of these things is very much part of the conversation, interwoven with the making of the fabrics and dresses, so it would be very challenging to tease those apart, to say where one thing stops and another thing starts. That’s one of the happiest natures of the relationship, is that it has become so deeply interwoven that each is a source for the other, quite literally.”

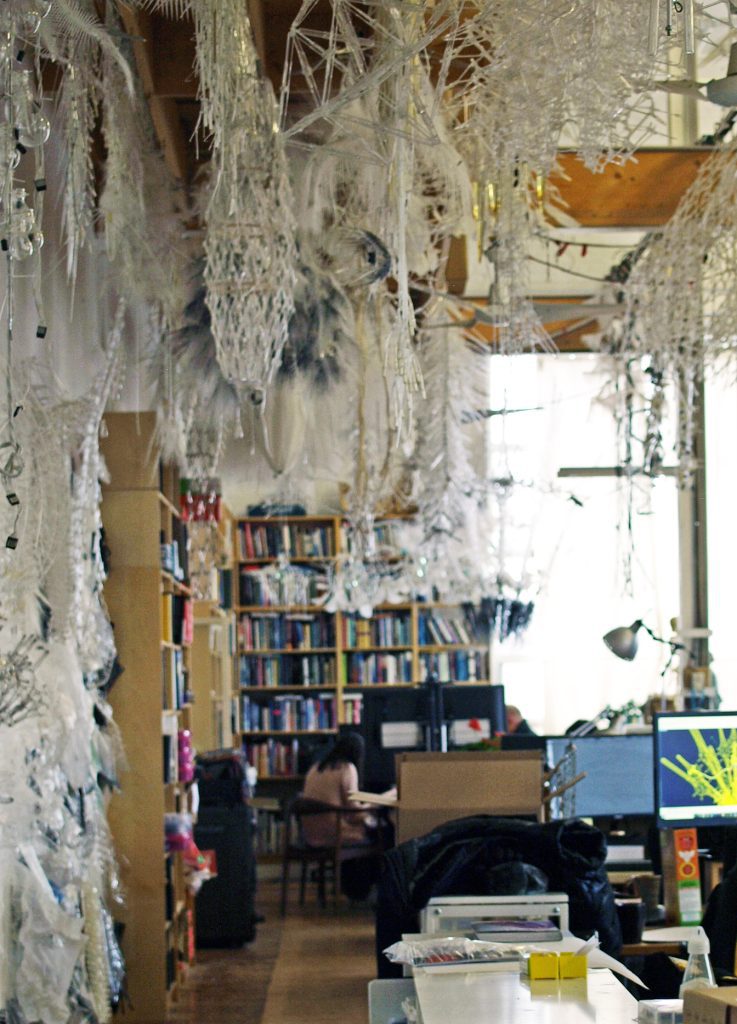

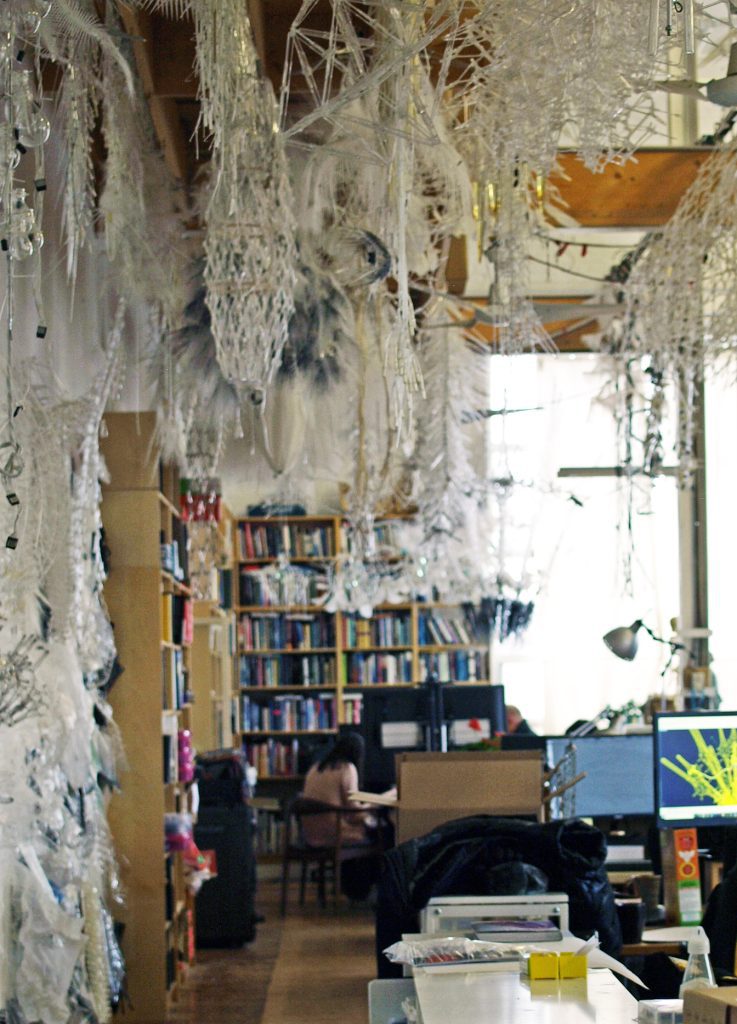

He admits that the design process naturally includes plenty of failure, trial, and error. Many of those tests and prototypes hang among the rafters and on the studio wall, which is covered with an expansive collage of newspaper clippings, metallic and polymer forms, feathery fronds, and clear baggies filled with seemingly random objects. Beesley notes that while it may take considerable effort to translate their ideas into fabrics, “the emergence of certain tools, such as computational design and the ability to prototype rapidly, means that a quality such as how something glistens or shimmers is not just mystified, but rather we can tune quite precisely some very subtle phenomena, and work at a very practical level with the part as well as the whole.” Instead of guesswork, technology lends precision to the process.

Beesley’s fascination with nature and how humans interact with the environment are a common thread whether he speaks of architecture or fashion. In fact, he sees the two fields as being intimately related. “When I think about the practice now, moving back and forth, I really can’t tell the difference – is there a difference between art and science, or fashion and architecture? They’re ones of scale and craft, but it seems like a very curious continuum to me.” And while he moves from one to the other, Beesley also moves between the realms of possible and impossible: “I work with both fact and fiction. I work with the fact of being very serious about the technologies, but then I step over into possibility crafting as well, in saying: Where could this go? How might we imagine possibility? I would say it’s that cycle between delivering strong technology and then imagining possibility that makes the dialogue with couture so particularly satisfying.”

Ultimately, Beesley’s interest in exploring the realm of responsive architecture, and fashion itself, seems to be in fostering connectedness. “Maybe that’s one of the largest hopes of this kind of work, is that we really can be interconnected this way – that something as deeply personal as the way I wear my collar offers a quality to atone to a cluster of people, which becomes a small group and a neighbourhood, and a people,” he explains. “Fashion is a particularly fertile place for this kind of development because there’s truly nothing more rigorous, even perhaps brutal in its honesty, than how it makes you feel and how your own body tests out its limits. I mean, what could be more acutely important, really, than the integrity of our own body and our own skin, and how we meet others and the world with that?”