Science has taken a psychedelic turn, showing promising results on mental health by way of LSD. Can the vilified substance break taboo to become the next wonder drug?

WRITTEN BY MIROSLAV TOMOSKI

Fifty years in the dark can do a lot for a reputation. It can breed a sense of mystery that captivates and terrifies, or it can drive us to discover more.

Nowhere has that veiled mystery done more damage than in the study of psychedelics. After half a century of hiding in the shadows, the future of these substances is brighter than ever. The relatively new field of psychedelic science is the key to an understanding of human consciousness. As this field of study is revived, the breakthroughs made by its modern pioneers have us all asking whether fifty years was far too long to spend in the dark.

After years of prohibition, science is finally beginning to explain the vibrant visuals and emotional responses induced by psychedelics. Much more than that, it’s reviving the medicinal properties that early researchers found promising.

MAPPING THE FUTURE

Within the US and Canada, the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Sciences (MAPS) is on the verge of receiving FDA approval of its MDMA-assisted therapy for patients with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). In late August, this treatment method received the FDA’s ‘Breakthrough Therapy’ designation – a major step in accelerating its clinical trials and eventual approval, which is expected to come by 2020.

A year ago, MAPS completed six trials in the US, Israel, Switzerland and Canada where patients with treatment-resistant PTSD found success with MDMA-assisted therapy.

The process is one in which patients undergo a regular therapy session, followed by two sessions in which MDMA is administered by their therapist. In their latest trials, which included 107 patients, MAPS found that 66 percent no longer qualified for PTSD after just two sessions.

The treatment, which is currently in its final phase of clinical study, has been fast-tracked by the FDA because of its immense success against a stubborn illness.

“Physicians and patients alike are at their wits end for better treatment for PTSD,” says Brad Burge, director of strategic communications for MAPS. “The idea that there could be a treatment that is effective after only a couple of sessions, rather than administering a drug every day for the rest of their lives, is extremely promising both for the treatment providers and the patients themselves.”

In the next phase, and with the Breakthrough Therapy designation, MAPS will continue their clinical trials and provide training for up to 100 therapists to be certified in administering MDMA. Part of that training is administering the substance to the professionals themselves so that they can understand what their patients are going through in their treatments. This is all part of the process of ensuring that an infrastructure exists to make the treatment widely available by the time it’s approved.

“The goal is to do enough public education and to help enough people learn about it and to train enough therapists so that by the time we have approval from the FDA, in about 2020, we can have a very fast rollout,” Burge says, insisting that the attitudes of officials changed as researchers began to see results.

Both the FDA and DEA have been receptive to MAPS studies in a way that could be considered unusual for such vilified substances. Part of that has been the organization’s risk management strategies, including a patient registry and a 5000-pound safe bolted to the floor, where a few grams of the purest MDMA in the world is kept.

As for its addictive qualities, Burge insists that there is no evidence that a few administrations of MDMA could cause dependence. Of the more than 100 patients who have received the treatment, he says only a few have sought out the substance outside of their clinical trials.

In these cases, the patients returned to MAPS with regret because simply taking MDMA is not what the treatment is about. The drug is only a catalyst or aid which allows the patient to become more receptive to regular therapy. This means that the setting is just as important as the drug itself.

“Engaging those issues outside of therapy can actually make it worse and most participants understand that it’s not about the drug, it’s about the therapy, the connection, and the work that you do,” Burge says. “That’s how we’re looking at the drug. Not as a treatment, but as a tool for facilitating the treatment.”

As a result of the breakthroughs made by MAPS, MDMA is likely to become a household name for those suffering from PTSD. It’s the path that many psychedelics are now taking and it bears a resemblance to the way in which cannabis found its way into the mainstream: first as a medicinal substance, then as a socially acceptable high.

But one psychedelic which still has a long way to go to climb out of the underground is a chemical compound that once showed the most promise: Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD). It’s widely known as the drug of choice for the counterculture of the ‘60s and a sure-shot way to induce insanity. Yet much of its fearful reputation has come from a decided lack of information rather than experience.

Out of the Dark

On April 19, 1943, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann synthesized LSD while studying ergot fungi for pharmaceutical company, Sandoz. The company initially had very little interest in the substance, but Hoffman was fascinated by it. His first major trip has now entered LSD folklore as Bicycle Day, in which Hoffman rode two-and-a-half miles home after accidentally absorbing the substance through his fingers. In his autobiography, LSD: My Problem Child, Hoffman describes his experience by saying:

“I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant to escort me home. On the way, my condition began to assume threatening forms. Everything in my field of vision wavered and was distorted as if seen in a curved mirror. I also had the sensation of being unable to move from the spot. Nevertheless, my assistant later told me that we had travelled very rapidly.”

The experience which Hoffman encountered was the result of double the regular ‘street dose’ of 100 micrograms. At the time, he and others in the scientific community believed that LSD simulated the effects of psychosis, as Sidney Katz of Maclean’s magazine outlined in his 1953 article, “My 12 Hours as a Madman.”

But Hoffman and others who took a closer look – as well as several doses of the drug – eventually discovered that it was much more than a simulated mental illness. It offered a greater connection to and understanding of human consciousness in a way that couldn’t be fully understood without the technology of modern science.

That’s where the Beckley Foundation of the United Kingdom comes in today. Their organization aims to bring science back into the world of psychedelics and are helping to revive the decades of lost research on the subject.

Two years ago, when I first spoke with Amanda Feilding, the director and founder of the Beckley Foundation, she explained that they had been testing the effects of psilocybin (the active chemical in magic mushrooms) on depression with remarkably promising results.

“Things have changed quite a lot,” she says excitedly. “Psychedelics have gotten a lot more acceptable largely due to our research.”

Scientists found that the results were not unlike those experienced by MAPS and MDMA-assisted therapy. When administered in a proper setting, those who had be diagnosed with severe depression found themselves more open and receptive to therapy. Now Amanda says her focus is squarely on LSD.

Having been immersed in the world of psychedelics since before they were outlawed, Amanda had taken part in some of the earliest studies. She’s witnessed first-hand the compound’s positive effects, as well as the years of misinformation that drove career-spanning research into obscurity.

The early days of psychedelic research were largely decentralized, with most research being done by scientists who had been captivated by the drug’s potential. While excessively relaxed in their regulations, these studies were very much in line with the practices of the day. Those loose methods produced now infamous psychological studies, like the Zimbardo Prison Experiment, which inspired modern ethical standards of practice. As Amanda points out, the concern with studies of the day was mostly with the result rather than the method. Yet those methods cost many their careers and, in hindsight, they cost substances like LSD their reputation.

CHAMPIONING A NEW ERA

Many who studied LSD were enthralled by its potential. The story of Timothy Leary, the pop scientist who famously invited the world to, “turn on, tune in, drop out,” is one that can be seen across the spectrum. Leary was ousted from Harvard University in 1963 for what can be seen as an excessive enthusiasm for the substance and off-campus dosing of unapproved clinical subjects.

It was this carefree way in which researchers used LSD, as well as its association with anti-war subculture, that would eventually have it classified under the highly-restrictive drug category of Schedule 1. But before Richard Nixon introduced the world to the Controlled Substances Act in 1970, LSD had a major role to play in the scientific community, particularly in psychology.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, more than 3000 research papers were published on the effects of LSD, while tests were conducted on 40,000 individuals around the world between 1950 and 1963. By 1955, Time magazine referred to LSD as, “an invaluable weapon to psychiatrists.”

Among these early researchers was Ronnie Sandison, whose work at Powick Hospital for the mentally ill is recognized around the world as a breakthrough in the treatment of mental illness. In an 11-year span from 1952 to 1963, Dr. Sandison worked with nearly 500 patients (administering micro-doses of 20 micrograms and regular doses of 100 micrograms) and discovered that the substance was far more effective than any conventional treatment.

Beyond Powick, Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, believed that alcoholics could benefit from a spiritual awakening. Far from the religious undertones which now permeate the program, the awakening Wilson was originally referring to was one which could be brought about by LSD.

At the time, alcoholics would undergo something known as delirium tremens, which induced states of distress in the patients similar to aversion therapy. But researchers in Canada felt that LSD could be used instead to accelerate the process while also eliminating the extreme discomfort patients often experienced.

Among these scientists was UK expatriate, Humphry Osmond (who also administered LSD to author Aldous Huxley). He championed LSD as a cure for alcoholism and coined the term psychedelic, which meant, ‘mind manifesting’.

Osmond had moved to Canada after his work was rejected in the UK and worked together with Canadian chemist Abram Hoffer at Regina General Hospital. By the 1960s, over 2000 patients had participated in their studies with over half remaining sober a full year after their therapies.

But these, as with other studies, were lightly controlled to the point that even nurses and hospital staff were participating while external factors such as music and environment were not taken into account.

Breaking Barriers

LSD had become a cultural icon of its own and, more importantly, it became associated with the counterculture. As the government and the public by extension began to drive that counterculture underground, the research went with it.

“If you wanted to kill your research career in academics, you did research on psychedelics,” Professor David Nichols of Purdue University told Popular Science in 2013. It wasn’t until the 1990s that organizations like MAPS and Beckley began to emerge through the cracks of taboo and investigate the positive effects of psychedelics.

Since its founding, the Beckley Foundation has sought to revive this lost field of study. With the use of modern scientific methods and technologies, Beckley has now brought a more rigorous scientific method to the research that preceded them.

“When I started the Beckley in 1996, I always wanted to bring the very best science to the psychedelic subject,” says Fielding. “I always knew that it was only with the very best science that we would break down the taboo and open up knowledge of how these substances work and why they’re so useful.”

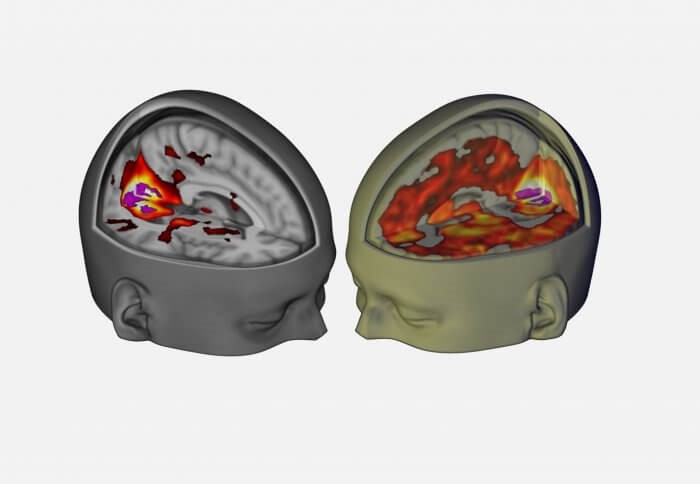

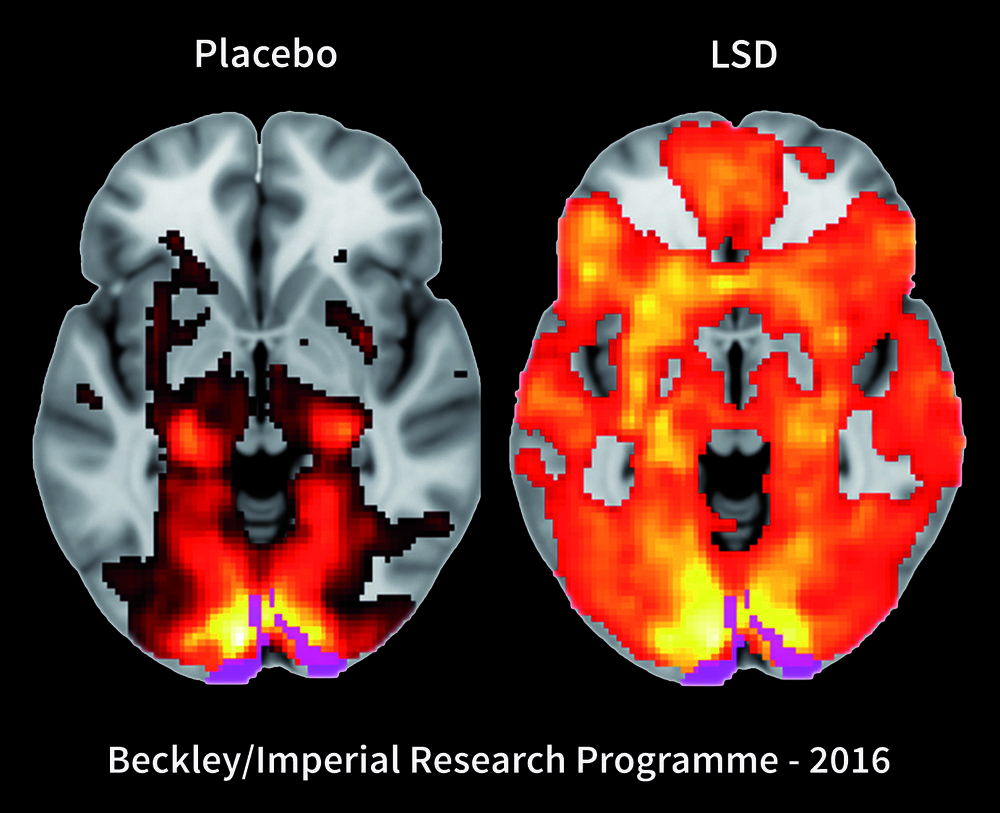

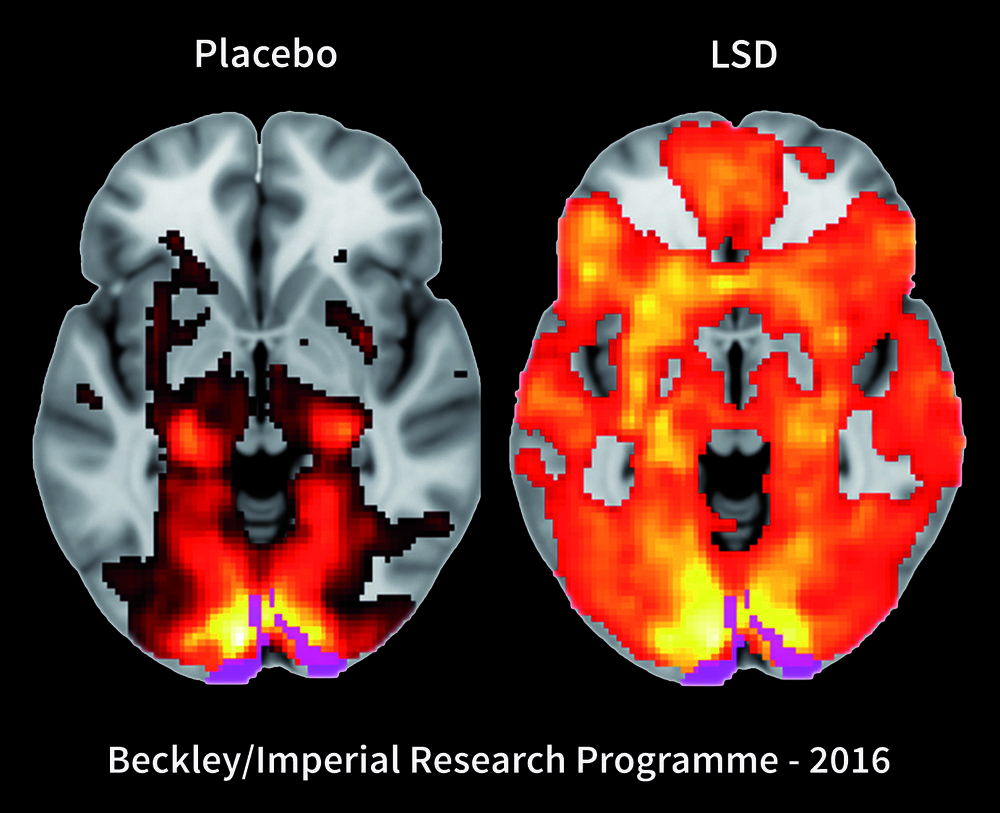

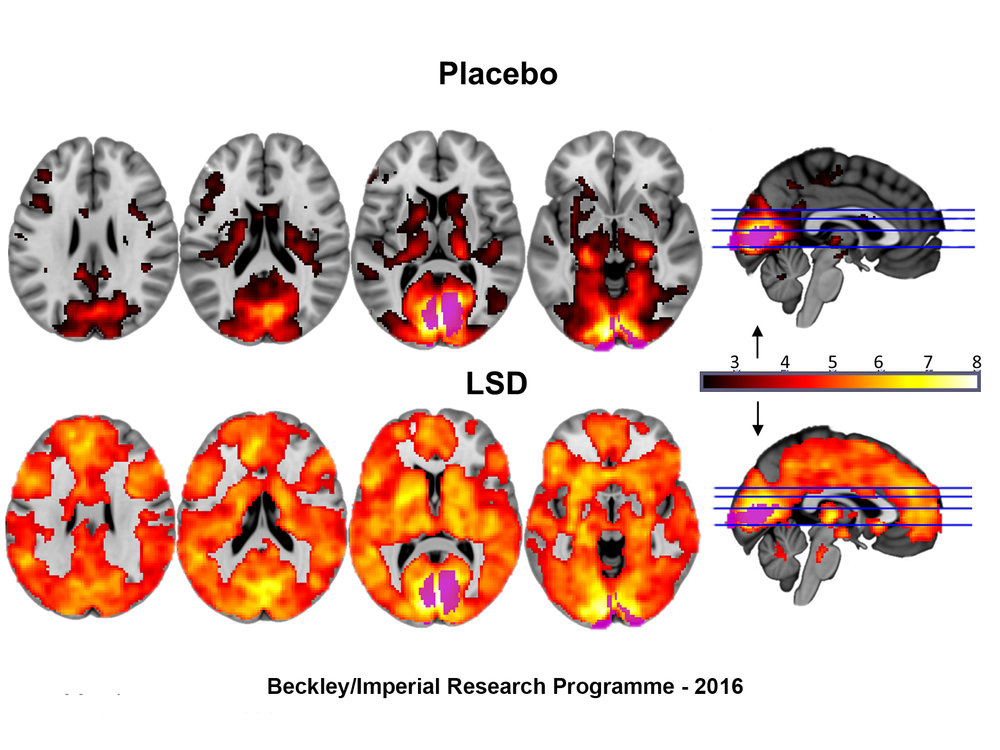

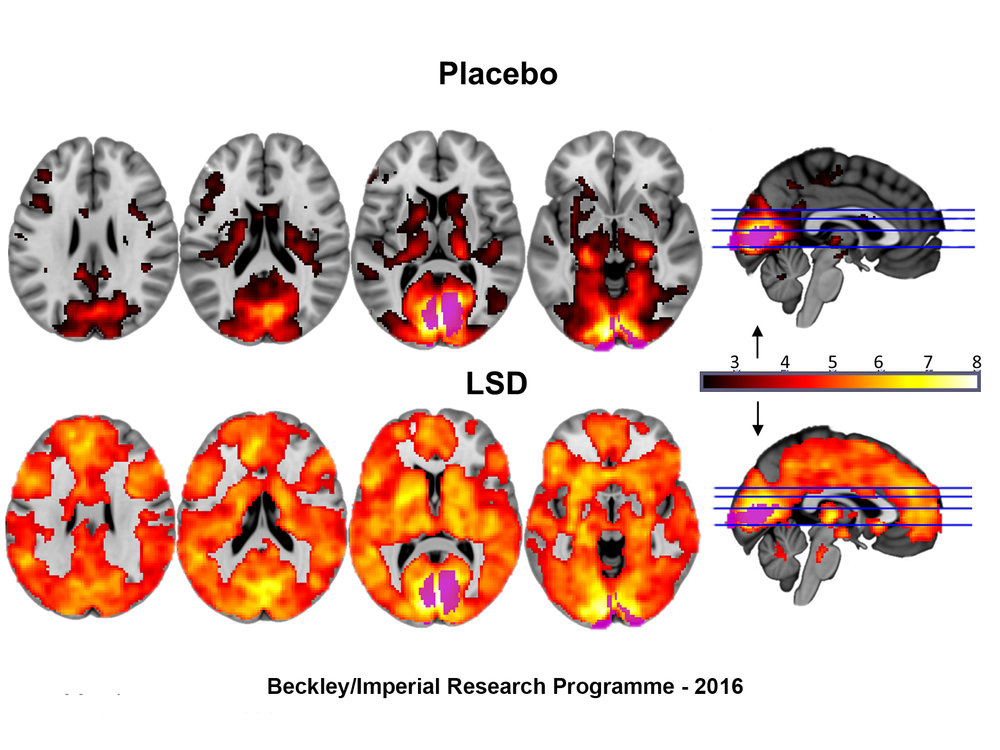

In 2015, the Beckley/Imperial College Research Programme gave the world the first images of the brain on LSD. The scans, which were conducted by 20 volunteers, used fMRI and magnetoencephalography (MEG) technology on subjects who received either 75 micrograms of LSD or a placebo.

The images, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed a stunning picture of the human brain in which something known as the Default Mode Network (DMN) had been dissolved.

“What a psychedelic does – and particularly LSD,” Feilding explains, “is reduce the level of blood supply to the Default Mode Network—which is the controlling repressive part of the brain—thereby allowing the whole brain to communicate with itself.”

In essence, the use of LSD breaks down the barriers in the brain which assign specific tasks to particular parts within the organ. It opens these channels and allows them to communicate with each other, permitting the brain to work more freely as a whole.

“It explains why there is a sort of rebooting of the personality” she continues. “Secondly, it explains why the experience is so much deeper and richer and why there’s a tendency to have more creative thoughts that sprout up because different parts of the brain are communicating with each other that don’t usually have a connective wiring.”

MYTHBUSTERS

But of course, when discussing LSD, we also have to consider a mythical experience which is the source of fear for many: flashbacks. Clinically known as Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD), the infamous acid flashback is a psychological reality. But its origins are far less understood than its myth.

A 2002 review of research from Harvard Medical School, titled Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years?, found several interesting facts about HPPD.

“It is often unclear whether symptoms occurred exclusively following hallucinogen intoxication. It is also difficult to rule out other medical or psychiatric conditions that might cause ‘flashbacks,’ including current intoxication with another drug, neurological conditions, current psychotic or affective disorders, malingering, hypochondriasis, or even other anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).”

Like many things about LSD, this experience too is plagued with serious misinformation or an entire lack thereof.

“We have to re-educate people because they’ve been terribly miss-educated over the last fifty years,” Feilding says. “They really believe the stories about psychedelics frying the brain. It’s been thrusted on people for so long they’ve really come to believe it.”

Rather than causing a haunting perpetual trip, what researchers at Beckley have found is the presence of an afterglow that is familiar to those who have taken the substance, but perhaps unclear or illusive in its origin.

“We’ve noted that several of our studies – from psilocybin to LSD and Ayahuasca – quite often have a very positive afterglow which can last weeks or months,” she points out, going on to say that the experience of psychedelics is far different from the chemically distinct effects of antidepressants.

“I think that is the problem of antidepressants,” Fielding says. “They are slightly clouding perception, whereas a psychedelic is more opening it up and hopefully enabling the patient to be more positive so they are approaching the problem in a different way.”

That is one reason she also believes that micro-dosing could be the key to mainstream acceptance of LSD. The practice, which only requires a barely noticeable dose of up to 20 micrograms, is already a popular method for increased productivity among programmers in Silicon Valley.

With the example set by tech workers, the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme will soon undertake the world’s first scientific study into the efficacy of micro-dosing. Using ‘Go,’ an ancient Chinese strategy game, they plan to investigate whether small doses of LSD can enhance intuitive pattern recognition and creativity. In addition to this, they’re reviving old theories of the effects of LSD on alcohol addiction with the benefit of modern technology and methods.

A Brighter Future

Admittedly, Feilding agrees that the biggest obstacle will be a shift in societal perception and allowing doctors to prescribe doses that a patient can take from home. But the progress made by researchers thus far has her cautiously optimistic for the future. In any case, she believes it’s better to take the leap then to never try at all.

“Everything has a little bit of risk, riding a bike, climbing a mountain, walking across the road,” she says.

Still, while Fielding hopes that one day psychedelics will make their way back into a world of open acceptance, she concedes that they are not for everyone. Her main goal is to educate those who do wish to accept Leary’s cosmic invitation and to ensure that they have a safe trip. Part of that safety will come from the information that organizations like Beckley can provide, such as proper dosing or the importance of maintaining blood sugar and vitamin C levels to quell a bad trip.

“It’s one of the essential bits of knowledge for the safe taking of psychedelics and that’s why I am very much in favour of moving towards a carefully regulated legal market,” she says. “For one thing, it would mean that what people are taking is what it says it is. Secondly the dose would be known. And finally, there can be instructions on how people should be taking it safely. It is available, as everyone knows, on the black market and through that you get the worst of all three.”

As psychedelics slowly make their way out of fifty years in the dark, organizations like MAPS and the Beckley Foundation are helping to shine a light and distinguish myth from fact. It’s a snail’s pace process, but one which promises to help millions suffering from mental illness, as well as those who have been stigmatized for their preferred state of mind. As Fielding says, it’s impossible to imagine that anyone would think of criminalizing different levels of consciousness. “Doing what you do in your own head is none of anyone’s business,” she says.