Written by Sabrina Maddeaux

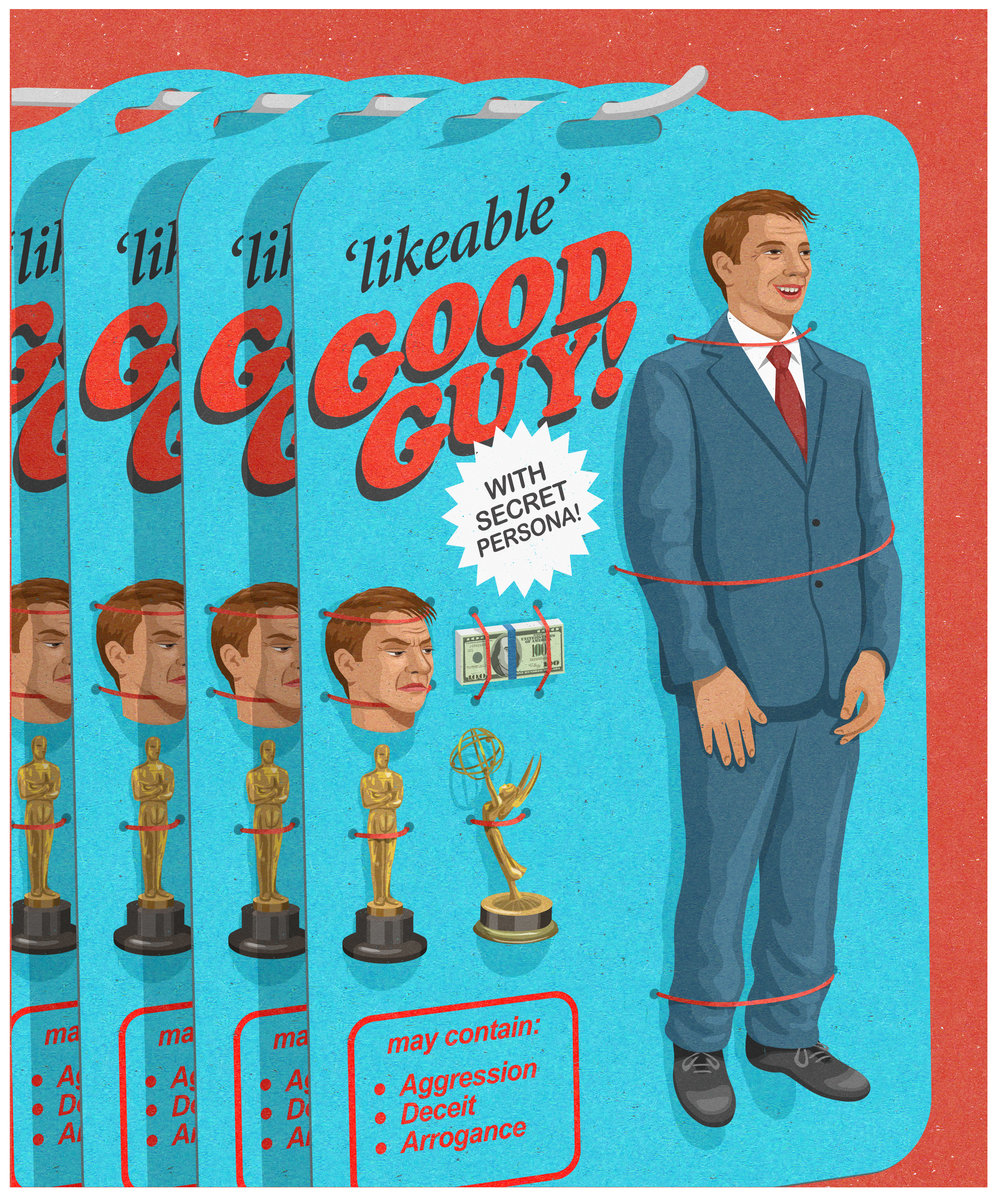

Illustration by John Holcroft

Harvey Weinstein was a bad guy, but what about all the nice guys? A look into the psychology behind why likeable men continue to get away with sexual assault.

Most people can agree that Harvey Weinstein is a bad guy. In recent months, allegations of sexual harassment, sexual assault, and bullying have piled so high it’s become hard to keep track. The allegations span decades and include a running list of Hollywood’s most recognizable names, like Rose McGowan, Ashley Judd, Angelina Jolie, and Gwyneth Paltrow.

Weinstein’s fall from grace has been relatively swift compared to other men accused of similar crimes and transgressions. Within days he was fired from his eponymous namesake business, publically denounced by his peers, and generally treated like a pariah. In the wake of the claims, The Weinstein Company has lost much of its financial backing and is considering a complete rebranding – including a name change – to distance itself from its disgraced founder and avoid a complete public relations disaster.

Most men accused of sexual harassment or assault suffer minute consequences in comparison — if any at all. Claims against the likes of Woody Allen, Ben Affleck, Casey Affleck, Bill Clinton, Kobe Bryant, Louis C.K. and more typically result in little more than hushed whispers of disapproval and maybe an unfavourable headline or two. Rarely are these men’s careers or lifestyles affected. Even those like Jian Ghomeshi and Bill Cosby, who do see the inside of a courtroom, rarely see the inside of a prison cell or abandonment by their legions of loyal fans.

So what’s the difference between Weinstein and the scores of other men accused of victimizing women? It’s not the number of allegations. Clinton, Cosby, Ghomeshi — and let’s not forget President Donald Trump – also have accusers well into the double digits. It’s not the severity or shock value of them, either. The most notable difference between Weinstein and many of these men is that he’s downright unlikeable. Even before the allegations made headlines, it was no secret that Weinstein was short tempered, volatile, egotistical, and frequently a bully.

(Some may argue Trump’s categorization as “likeable,” but the 45th president of the United States is widely acknowledged to be charismatic and, as a former reality TV star, had to come across as at least somewhat affable for years.)

The chasm between how we respond to accusations against likeable men and unlikeable ones stems from social categorization – something psychologists say we do unconsciously as a mental shortcut. It allows us to infer someone’s qualities and characteristics based on those of others in the same grouping. Once we categorize someone, we begin to think of them in context of a larger group rather than as an individual. This is also the cognitive process responsible for stereotyping.

Problematically, once we psychologically categorize someone as “likeable” we have a hard time reconciling them acting in unsavory ways. John is no longer just “John” – he’s one of the good guys. And “good guys” don’t assault women. When evidence or accusations to the contrary arise, we struggle to separate them from the larger group and throw our entire categorization system into question.

Convicting Weinstein is an easier cognitive process because many people already categorized him as a bad guy. It’s not farfetched that a bad guy may harass or attack someone.

Moreover, in a culture that equates thinness, strong jawlines, and full heads of hair with likeability, Weinstein looks unlikeable. It’s noteworthy how many of his accusers and detractors mentioned his physical appearance. Italian actress Asia Argentno described her assault as “twisted. A big fat man wanting to eat you. It’s a scary fairytale.”

Harvey’s unlikeableness, inside and out, made it easier for people to believe the accusations and root for his downfall. However it’s a different story when a predator is handsome, charismatic and generally well-liked.

Many studies have shown the advantages of being beautiful; it can help you land a job, find a mate, get a raise, and even get elected to political office.

Researchers dub this advantage as a “beauty premium” or the “attractiveness halo” that applies to basically all parts of life. Disturbingly, being beautiful can also help you get way with predatory behaviour.

Unlike Weinstein, Ghomeshi was described as “scruffy and handsome” and “charismatic” in coverage of his trial. Cosby was described as “good-looking,” “handsome” and “funny.” It’s no big secret that Affleck, Leto, and Bryant are as conventionally good-looking as it gets.

Dr. Gordon Patzer, founding director and CEO of the Chicago-based Appearance Research Institute (ARI), has studied the subject for over three decades and published over six books and 20 peer-reviewed articles in research journals on the subject. He says, “Good-looking men and women are generally regarded to be more talented, kind, honest and intelligent than their less attractive counterparts.” A 2010 University of British Columbia (UBC) study published in Psychological Science, one of the most influential journals in psychology, backs up his research. UBC researchers found people are hardwired to display a positive bias towards attractive people. We have a harder time imagining good-looking men – particularly white men – doing bad things, and are more likely to believe them when they say they didn’t do it. We give them the benefit of the doubt.

Notably, this doesn’t hold true for women. No matter how likeable or attractive a woman is, she’s never above being labelled a slut, liar, or gold digger when she dares oppose a popular man. Our man-made cultural bias against women is so powerful that it overrides the hardwired instinct to trust attractive women. Unattractive and unagreeable women are even more easily dismissed.

The likeability and attractiveness issue doesn’t just come into play when accusing celebrities, politicians, and CEOs of assault. It also applies to everyday men, like your friendly coworker or socially-progressive best friend.

The Weinstein scandal spurred an online movement where countless women shared their own experiences with sexual harassment and assault using the hashtag #MeToo on social media. It quickly became clear that almost every woman has personally experienced unwanted advances in the workplace: groping, catcalling, flashing, sex acts without consent, and/or rape. Most women had more than one story to share.

While many men commiserated with their female family members, friends, and colleagues, and even expressed outrage, few seemed to have any idea about the prevalence of the problem. Even fewer seemed to know a fellow man who acted inappropriately around women, let alone committed a crime.

Clearly the math doesn’t add up. If almost every woman has been harassed or assaulted, it doesn’t follow that none of the men in their familial, professional, and social circles have been an aggressor or known an aggressor.

Most men aren’t purposefully sheltering abusers or covering up for rapists; rather, they’re letting unconscious biases blind them to the harsh realities of this widespread problem. For the most part, we consider friends, family, and even colleagues to be likeable and trustworthy characters. We categorize them in ways that make it hard to believe they’d do anything wrong.